No, the label Champagne hasn’t been confiscated by Russia!

From now on, I guess I’d prefer the Russian propaganda and check their claims rather than assuming that the Western disinformation is anything but a too hot Cold War. Vladimir Vladimirovich doesn’t need me as his pro bono attorney, but I hate any and all fake news, so here’s what you should know about the new “sparkling wine” war.

1·Western Fake News (mostly by omission)

Last week, and I literally mean seven days ago, I ran over such titles:

Moet to Label Its Champagne Sparkling Wine in Russia to Meet Law

The Champagne houses of Moet Hennessy will soon include a “sparkling wine” mention on their bottles shipped to Russia to respect a new law that reserves the name of the French region for bubbly wines made in the former Soviet country.

The legislative change that requires the “sparkling wine” mention on the label on the back of Champagne bottles is leading to a “very temporary suspension of deliveries” to adjust from a logistics and regulatory point of view, Moet Hennessy — part of luxury group LVMH — said in a statement to Bloomberg on Sunday. Shipments will resume as soon as possible, once these adjustments are made.

Vladimir Poutine a donné son feu vert, vendredi 2 juillet, à un amendement de la loi sur la réglementation des boissons alcoolisées qui fait réagir en Russie… et en France. Selon ce texte, seuls les producteurs russes auront désormais le droit d’afficher l’appellation « champagne » sur leurs bouteilles. Les vins importés devront, eux, signifier une appellation « vin à bulles ». Cet amendement indique clairement que la législation russe ne tiendra pas compte de la protection de l’appellation française « champagne AOC ».

En réaction à cette décision, le Français Moët-Hennessy a suspendu, le temps d’un week-end, ses exportations vers la Russie. Dans un courrier destiné à ses clients russes et auquel le quotidien économique Vedomosti a eu accès, la société française a annoncé devoir réaliser une nouvelle certification de ses produits, qui devrait coûter plusieurs millions de roubles.

Ayant accepté, dimanche 4 juillet, de se plier aux requêtes russes, elle doit changer ses étiquetages et renommer ses produits dans le respect de la nouvelle législation. Le quotidien russe rappelle que 13 % des 50 millions de litres de mousseux et champagne importés chaque année en Russie viennent de France. Moët-Hennessy représente 2 % de ce marché.

Une AOC menacée dans le monde entier

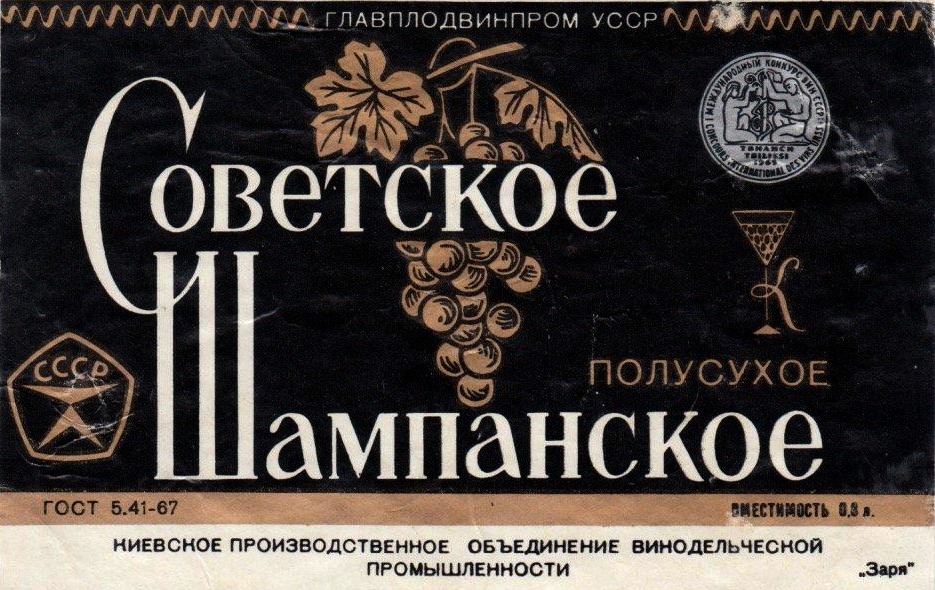

En Russie, cela fait longtemps que le terme « champagne » est utilisé sans complexe et pour toutes sortes de vins à bulles. Staline fit créer à la fin des années 1930 un « champagne soviétique » produit en masse, avec l’objectif de le rendre accessible à tous.

Au lendemain de la chute de l’URSS, ce « champagne soviétique » est devenu une marque synonyme de mousseux bas de gamme, mais toujours aussi populaire lors des grandes occasions. Un état de fait qui n’a jamais ravi les producteurs champenois, défendus par le comité interprofessionnel du vin de champagne (CIVC), et qui mènent depuis de nombreuses années une bataille destinée à protéger cette appellation contrôlée menacée dans le monde entier.

Comment la Russie s’approprie le champagne

Vladimir Poutine veut réserver l’appellation « champagne » à des mousseux produits en Russie. Un affront pour les producteurs français, qui vont devoir changer leurs étiquettes s’ils veulent conserver le marché russe.

La Russie et l’art de vivre à la française, c’est une longue histoire d’amour, mais elle ne manque pas de coups un peu vaches. Depuis ce vendredi, une nouvelle réglementation sur les boissons alcoolisées est d’application dans le pays. Sauf que selon ce texte, l’appellation « champagne » ne pourra plus être arborée que par les producteurs russes ! Les bouteilles venues d’autres pays devront se contenter d’appellations de type « vin à bulle » ou « vin mousseux ». Pour la France, patrie de la véritable méthode champenoise, c’est un innommable sacrilège autant qu’un terrible manque à gagner.

Patrimoine viticole

On l’oublie parfois, mais la vieille Russie est depuis longtemps une terre de vignes, dans le Caucase et sur les bords de la mer Noire, entre autres. C’est même sans doute de cette région qu’est originaire le raisin et sa culture. Au XIXe siècle, les Tsars cherchent à produire des alcools de luxe équivalents en qualité à ceux du terroir français, des vins, mais aussi des équivalents du cognac dans les actuelles Arménie et Moldavie. Mais ce patrimoine viticole faillit disparaître dans les flammes de la révolution bolchévique. Jusqu’à être totalement galvaudé: dans les années 1930 apparait le « Champagne soviétique« , produit en masse sous l’impulsion de Staline, qui veut en faire un produit accessible à tous et un symbole de la supériorité du communisme sur l’occident capitaliste.

Une appellation qui fait grincer des dents les producteurs de vrai champagne, d’autant plus quand, après la chute de l’URSS, différents producteurs de l’ancien bloc de l’est reprennent ce nom, au mépris total des normes d’appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC). Là encore, le champagne n’est pas le seul breuvage concerné : l’Arménie et la Géorgie restent très attachées à leur « cognac », d’ailleurs réputé, et refusent de le rebaptiser « brandy », le terme générique pour ce genre d’alcool. La décision de Vladimir Poutine de réserver le mot champagne à des mousseux nationaux est un camouflet au régime AOC, et un rejet des négociations précédentes sur ce sujet.

Quoiqu’en pensent les producteurs français, ils vont devoir s’adapter s’ils veulent rester présents sur le marché russe. La société Moët-Hennessy a suspendu ses exportations vers le pays. Pas en protestation, mais pour rendre son marketing conforme aux nouvelles normes russes. Les prestigieuses bouteilles françaises réapparaitront donc bientôt chez les cavistes russes, mais avec de nouvelles étiquettes. Une opération qui coûtera plusieurs millions de roubles, selon le quotidien économique Vedomosti. Qui rappelle aussi que 13% des 50 millions de litres de mousseux et champagne importés chaque année en Russie viennent de France.

2·Russian Confusion (mostly because there’s no censorship in Russia)

The Russian online media is as stupid as everywhere. OK, in Eastern Europe (even in Romania, which wasn’t part of the USSR) the online is on average worse than in Western Europe, almost everything looking as if it were Facebook or Daily Mail. So one could find plenty of similar disinformation that simply conveyed the message coming from the whining LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, formerly Moët & Chandon.

Say, В Moët & Hennessy согласились изменить маркировку поставляемых в Россию напитков, automated translation:

On July 2, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed amendments to 171-FZ on the regulation of alcoholic beverages, which introduce additional requirements for alcohol. In particular, the law now allows the use of the name “champagne” only for Russian products. In this case, wines from the French Champagne region will have to be renamed “sparkling wine”.

Champagne Moët & Chandon, Dom Perignon, Veuve Сlicquot and others are produced by the world’s largest luxury goods manufacturer – LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton.

3·The Truth (which is complex and nuancé)

Izvestia is one of the major newspapers that published pertinent explanations; here you have excerpts, with automated translations: In Russia there is not and will not be a ban on the use of the word “champagne” on the labels of foreign manufacturers:

The law “On viticulture and winemaking in the Russian Federation”, which began to operate on June 26 last year, introduced a classification of wine products, including wines, sparkling wines, fortified wines, the Ministry of Agriculture recalled.

On July 2, corresponding amendments were made to Federal Law No. 171-FZ on Alcohol, which provides for a similar classification based on international standards, the press service of the department explained to Izvestia.

If the manufacturer has registered in the prescribed manner a geographical designation for wine products, including Champagne, then the law does not contain a prohibition on its use. At the same time, an indication of the type of wine on the label is mandatory.

All the adopted amendments to 171-FZ are only the harmonization of its requirements with the already functioning law on viticulture and winemaking (468-FZ) in the Federal Alcohol Market Regulation, emphasized the source of Izvestia. Both documents regulate the production and circulation of wine products. Considering that 468-FZ entered into force in the middle of last year, it is surprising why the French company did not express concerns all this time, the source said.

Neither 468-FZ nor 171-FZ prohibit foreign producers from writing the name of the drink on the label, namely champagne, Dmitry Kiselev, chairman of the council of the Union of Winemakers of Russia, told Izvestia.

Only on the back label of the bottle should it be indicated that this is sparkling wine (and this is an international classification), after specifying the region (Champagne), he added. The regulation does not pose any significant burden for importers, they only need to go through formal procedures for re-certification of products.

The words “sparkling (champagne)” have been replaced by the word “sparkling” in the text of Law No. 171, since they are not synonyms: sparkling is not always from Champagne, the expert specifies.

Now producers of ‘champagne’ from outside of Champagne must indicate on the label e.g. “Sparkling wine. Place of production: Alsace,” explains Dmitry Kiselev. Producers of Champagne sparkling wine must indicate “Sparkling wine. Champagne.” These rules fully comply with world practice and exclude consumer misleading about the place of wine production, which is done, among other things, in the interests of the producers of “real champagne” from Champagne.

In the case of the concepts of “sparkling wine” and “Russian champagne,” we are talking about the types of alcoholic products that must be indicated in Russian, but on the counter-label with the help of an additional sticker, explained Alexander Stavtsev. Nobody can change names and trademarks in other languages on the bottle, he noted.

In the case of champagne and sparkling wine, this is GOST [Russian technical standard] for sparkling wines, and drinks should be conforming. The standard has not changed, added the [representative of the] organization.

Some links to the relevant Russian legislation:

- Законопроект № 226620-7 О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон “О государственном регулировании производства и оборота этилового спирта, алкогольной и спиртосодержащей продукции и об ограничении потребления (распития) алкогольной продукции и отдельные законодательные акты Российской Федерации” — Bill № 226620-7 On Amending the Federal Law “On State Regulation of the Production and Turnover of Ethyl Alcohol, Alcoholic and Alcohol-Containing Products and on Restricting the Consumption (Drinking) of Alcoholic Products and Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation” (on improving the legislation regulating viticulture and winemaking in the Russian Federation)

- Федеральный закон от 22.11.1995 № 171-ФЗ (ред. от 02.07.2021) “О государственном регулировании производства и оборота этилового спирта, алкогольной и спиртосодержащей продукции и об ограничении потребления (распития) алкогольной продукции” — Federal Law of 22.11.1995 № 171-FZ (as amended on 02.07.2021) “On state regulation of the production and circulation of ethyl alcohol, alcoholic and alcohol-containing products and on limiting the consumption (drinking) of alcoholic products”

- Федеральный закон от 27.12.2019 г. № 468-ФЗ О виноградарстве и виноделии в Российской Федерации (В редакции Федерального закона от 08.12.2020 № 429-ФЗ) — The Federal Law № 468-FZ On viticulture and winemaking in the Russian Federation (As amended on 08.12.2020 by Federal Law № 429-FZ)

The above legal texts are not on the same website, but don’t ask me to be familiar with the entire network of official websites. I just used Yandex a bit.

4·Explanations (not for those who are completely retarded or brainwashed)

The situation is as follows:

- The original French bottle of Champagne don’t have to change their labels! What needs to be added is a secondary label or an additional sticker, in Russian, with the words «Игристое. Шампань». Similarly, a Crémant d’Alsace should have an additional label or sticker in Russian saying «Игристое. Место производства — Эльзас».

- Note that «Игристое» means “sparkling wine” or “mousseux” — but including the original sparkling wine made in the region of Champagne, which legally bears the name “Champagne AOC.” It’s meant for the internal Russian market only, and it must be in Cyrillic.

- The classification is made in the law № 468-ФЗ from end-2019, amended end-2020.

Art. 2 deals, among others, with:

28) wine with a protected designation of origin – wine, fortified wine, sparkling wine …

34) sparkling wine – … obtained as a result of primary or secondary alcoholic fermentation of fresh grapes, grape must or wine that, when opening the container containing it, releases carbon dioxide, formed exclusively as a result of alcoholic fermentation, due to the content of carbon dioxide in a closed container with an overpressure of at least 300 kilopascals at a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius and the total volumetric content of ethyl alcohol that should not be less than 8.5 percent;

57) Russian wines of protected appellations – wine, fortified wine, sparkling wine with a protected geographical indication and (or) with a protected appellation of origin within the framework of the Russian national system of wine protection by geographical indication and place of origin;

58) Russian champagne – sparkling wine produced in the territory of the Russian Federation from grapes grown in the territory of the Russian Federation by the method of secondary fermentation of the cuvée obtained from it in containers that are packaging for their retail sale;

Art. 18 further subdivides the sparkling wines:

4. Generally:

1) aged sparkling wine – sparkling wine aged after the end of secondary fermentation for at least six months;

2) Russian champagne aged – Russian champagne aged for at least nine months after the end of secondary fermentation in containers that are packaging for their retail sale;

3) Russian collection champagne – Russian champagne aged for at least thirty-six months after the end of secondary fermentation in containers that are packaging for their retail sale.

5. By sugar content:

1) extra brut – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars less than 6.0 grams / cubic decimeter;

2) brut – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars from 6.0 to 15.0 grams / cubic decimeter;

3) dry – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars from 15.0 to 25.0 grams per cubic decimeter;

4) semi-dry – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars from 25.0 to 40.0 grams per cubic decimeter;

5) semi-sweet – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars from 40.0 to 55.0 grams per cubic decimeter;

6) sweet – sparkling wines with a mass concentration of sugars from 55.0 grams per cubic decimeter. - The new labeling, according to the same law № 468-ФЗ (all alcoholic products), is described in “Article 26. Peculiarities of labeling and retail sale of wine products.” This was known for more than 6 months already! Basically, what has to be mentioned is the variety or varieties, the place of origin and the vintage of grapes in a font not smaller than 14pt; then, the sparkling wines produced in Russia have the right to be labeled as “Russian champagne.”

- The labeling is also addressed by the older law №171-ФЗ (wine products), in Art. 11 §3 (the information that accompanies an alcoholic product) and in Art. 12 (the labeling itself, very similar to law № 468-ФЗ, Art. 26). The provisions of the two laws have just been harmonized (i.e. synchronized), and Moët & Chandon didn’t see it coming!

- I don’t see and problem in the fact that the Russian translation of “Champagne AOC” is not accepted in Russia, so the original French text should have an additional Russian one that translates to “Sparkling wine from Champagne”; and conversely, that the Russian classification “Российское шампанское” is not recognized in the West in its translations “Russian Champagne” or “Champagne russe”; it’s a matter of jurisdiction, territoriality and national sovereignty.

Much more delicate is the problem of the cognac or, of the коньяк, regulated in Russia by the aforementioned law №171-ФЗ at Art. 2, 10.1):

cognac – an alcoholic drink with an ethyl alcohol content of at least 40 percent of the volume of finished products (except for cognac with a protected geographical indication, cognac with a protected appellation of origin, collection cognac), which is produced from cognac distillates obtained by fractional distillation (distillation) of wine materials made from grapes and aged in oak barrels or oak buttes or in contact with oak wood for at least three years. Cognac with a protected geographical indication, cognac with a protected designation of origin, collection cognac must have an ethyl alcohol content of at least 37.5 percent of the finished product. The cognac distillate, which has been aged for more than five years, is aged in oak barrels or oak buttes.

Frankly, I’m with Vladimir Vladimirovich on this one. Russia should be free to use the term коньяк on his territory. The French Cognac AOC shouldn’t mean everybody else must use the term brandy exclusively. This is absurd, as brandy strongly suggest an American thing, which it isn’t in the case of a European or Asian one!

Let me ask you these questions:

- Are we allowed to use the common noun and the verb xerox, or the use of photocopy is mandated by law?

- Are people in France allowed to use the common noun scotch and the verb scotcher, and the Italians and the Romanians the noun scotch, or is adhesive tape mandated by law? Same question for sellotape (noun and verb) in British English.

- Are we allowed to use the verb google, even if we actually binged, duckduckwent (sic!) or yandexed something, or must we say we performed a Web search?

Now you have your answer. The entire Central and Eastern Europe, plus the Soviet Union, have used the generic terms of champagne and cognac for many decades, and not only in the times of the Communist Regimes. As a proof, look into other languages, and you’ll find Kognac and Champagner in German; conhaque and champanhe in Portuguese; coñac and champán in Spanish; κονιάκ and σαμπάνια in Greek; konjakki and samppanja in Finnish; konyak and şampanya in Turkish; and back to some former Communists, coniac și șampanie in Romanian.

5·Take-Home Message

👉 Russia didn’t confiscate the term Champagne.

👉 Russia didn’t forbid LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton to use the term Champagne (Latin letters, not Cyrillic!), nor did Russia force them to change their labels of Champagne AOC; what Russia now mandates is the addition of an extra sticker or label in Russian.

👉 Russia did reserve the right to use for their national products the terms российское шампанское (see № 468-ФЗ) and коньяк (see №171-ФЗ), but this isn’t what LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton complained about in the first place.

Leave a Reply