Yoga, 4-6, 4-7-8 and 4-8 Breathing, and the retarded Dr. Weil

Breathing is something we don’t properly do anymore, even as it’s crucial to keep being alive. Modern life has made us unable to even breathe correctly! The ancient philosophy of Yoga includes in its various practice systems several breathing exercises. The very least we should learn from this ancient discipline is breathing! And several medical doctors have actually built a fame on borrowing from Yoga.

Introduction

For us, those who are not into Yoga, a good (and neutral) starting point would be James Nestor’s book, Breath: The Science of a Lost Art. I learned about it at the same time I learned about Patrick McKeown, self-declared expert in the field of breathing and sleep.

I’m not saying that Patrick McKeown is a charlatan. He’s even a fellow of the Royal Society of Biology in the UK. But his only studies are in “Business, Economic and Social Studies, Political Science and International Marketing” at Trinity College, Dublin, 1992-1997. This is something politicians do, as it’s an umbrella that covers a lot, and not much of anything, actually. Somehow, he managed to be the creator, CEO and Director of Education and Training at Oxygen Advantage® (a world-leading breathwork training program), Director of Education and Training at Buteyko Clinic International, and author of books such as The Breathing Cure and The Oxygen Advantage®. And competent enough, in the opinion of the Royal Society of Biology.

Still, The Breathing Cure is educational. You’ll find that breathing 6 times per minute brings more air to your lungs than breathing 12 times per minute. You’ll learn about the biochemical aspect of breathing, and of the importance of CO2. And you’ll learn about his breathing exercises (Light, Slow, and Deep).

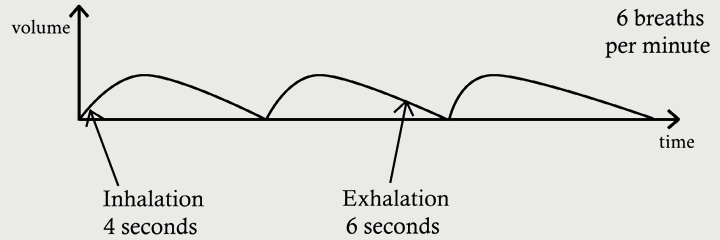

His “slow breathing” of 6 breaths per minute is a 4–6 cycle: 4 seconds for inhalation, 6 seconds for exhalation. Normal breathing is considered to happen 12 times a minute.

To “activate” your diaphragm, he wants you to (purchase and) use the Buteyko Belt, but you can do without making this guy rich.

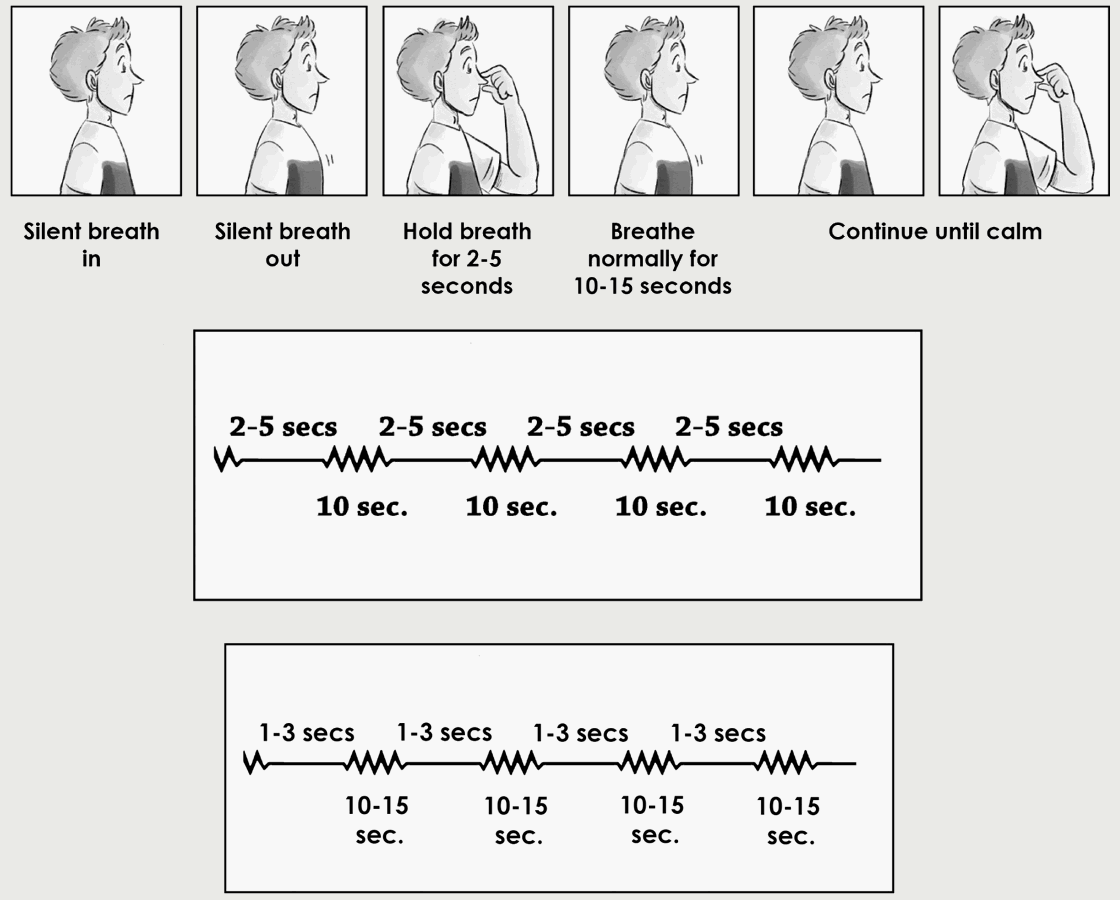

Another quick take from this book: an exercise to stop the anxiety. Hold your breath for 5 seconds (2 to 5 seconds), breathe normally for 10 seconds (through your nose), and repeat the sequence as long as you need. In the case of a panic attack, the exercise is changed to: hold your breath for (up to) 3 seconds, breathe normally for 10–15 seconds (through your nose), and repeat until the symptom is gone. For the 10-second breathing, the 4–6 cycle can be used; for a 15-second breathing, it’s not specified.

There are also more complex training programs (including e.g. walking) for different medical conditions, but I haven’t explored them all. And I’m sure he reserves the best for his paying customers.

Enter Dr. Weil

This guy isn’t a quack or a fraud either, but he’s still sort of an idiot. He’s cited in connection with the so-called 4–7–8 Breathing Technique. Here’s a description of the said technique:

One cycle of the 4-7-8 breathing control included the following steps:

(1) Let the lip part make a whooshing sound and exhale completely through the mouth;

(2) close the lips, inhaling silently through the nose, count 1–4 in mind, and then hold breath for 7 seconds; and

(3) make another whooshing, exhaling from the mouth, and count 1–8 in mind.

Repeat the 4-7-8 breathing control for six cycles/set, for three sets interspersed between each set by 1-min normal breathing.

This description is taken from: Effects of sleep deprivation and 4‐7‐8 breathing control on heart rate variability, blood pressure, blood glucose, and endothelial function in healthy young adults (doi: 10.14814/phy2.15389). You’ll notice two things about these scientists:

- They can’t say “inhale for 4 seconds, hold your breath for 7 seconds, exhale for 8 seconds” without adding stupid mentions of what to do with your lips, and how to count in your mind. Note that a cycle takes 19 seconds, so you can breathe about 3 times per minute.

- What is a set? If a set means 6 breathing cycles (about 2 minutes), and you do “3 sets” (18 breaths) + 1 minute normal breathing + “3 sets” (18 breaths), why are they counting in sets of 6 cycles, instead of sets of 18 cycles, i.e. “18 slow breaths + 1 minute of normal breathing + 18 slow breaths”?

Idiots galore. But their beloved Dr. Weil is even worse. Take a look at this video: Dr. Weil explains how to do his 4-7-8 breathing technique. Yup, the maestro himself.

This idiot cannot observe the breathing pace advertised by the method he claims to have invented! Count for yourself: sometimes those 7 seconds are 3 and half. Sometimes the ratio 4:7:8 is not observed at all. You cannot practice this method by repeating what you see on the screen!

Some viewers found themselves puzzled, and one suggested that counting should not be second-based, but using half-seconds:

@kellybrennan5514: It’s around half a second for each count. The more you practice, the easier it will become.

@LZarbetski: So it’s really 3.5 and 4 seconds/hold and exhale? I have watched his video several times and the count isn’t in full seconds. So what is the real deal?

@anticorncob6: That makes absolutely no sense. How can you breathe in slowly for four seconds and then breathe out rapidly for eight?

Of course it doesn’t make any sense. There are a bazillion of videos about this technique. Use any of them, but this one!

The aforementioned study says it clearly: counting is in seconds. But I find it extremely difficult to hold my breath for 7 second, then to exhale as slowly as in 8 seconds. It’s mission impossible!

Apparently, the inhale:exhale ratio = 1:2 is important (the 4–8 part, as opposed to 4–6 encountered at our Irish guy):

In practicing the 4‐7‐8 breathing control (inhale:exhale ratio = 1:2), participants’ respiratory rate was approximately 3 breaths/min. This breathing pattern is similar to deep and slow breathing, which has previously been investigated. … These data could confirm that slow breathing control enhances parasympathetic activity and lowers BP. However, Chinagudi et al. (2014) demonstrated that in healthy adults with sympathetic predominance, high‐frequency power in normalized units significantly decreased, whereas low‐frequency power in normalized units and low‐ to high‐frequency ratio significantly increased after slow and deep breathing at 6 breaths/min for 5 min. However, in their study, the inhale/exhale ratio was 1.

The aforementioned data suggest that parasympathetic activity is augmented by breathing with a low inhale/exhale ratio. Moreover, additional holding of one’s breath during inhalation can increase arterial oxygen saturation and subsequently decrease peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation, thereby enhancing the parasympathetic activity and lowering the BP (Turankar et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2019). Notably, our study revealed that in the control group, significant decreases in low‐frequency power, low‐frequency power in normalized units, and low‐frequency to high‐frequency ratio following the 4‐7‐8 breathing control indicate less sympathetic activity.

So, whatever parasympathetic activity were they considering, its improvement is optimal with longer exhalation times than the inhalation time, and furthermore by the stage when you hold your breath!

Anyway, what are the overall benefits of this thing? From the conclusions:

…by increasing parasympathetic activity and decreasing sympathetic activity, the 4‐7‐8 breathing control may improve HRV [heart rate variability] and BP [blood pressure], especially in people without sleep deprivation. This intervention may also be beneficial for patients with cardiovascular disease or pulmonary disease in terms of reducing cardiac work and enhancing blood oxygenation.

After 4–6 and 4–7–8, how about 4–8?

The part where you hold your breath is not completely disregarded in the 4–6 cycle, but it’s only recommended to get rid of anxiety, stress, or a panic attack. However, 4‐7‐8 cycle is impossibly slow, and breathing as slow as 3 times per minute looks crazy to me!

Incidentally, I found on YouTube a Yoga instructor from Wyoming. Not particularly smart, but useful. Here’s a selection of four videos with this guy:

- 4–4 breathing practice at minute 5:52: How to Naturally Increase Oxygen – 2 Breathing Exercises

- 4–8 breathing practice at minute 10:16: Improve your Sleep – 5 Proven Strategies

- 4–8 breathing practice at minute 12:40: Fix Your Sleep – Practical Tips to Improve Duration & Quality

- Wired, but tired? Try the Pranayama breathing practice at 09:50: Vagus Nerve Stimulation – 3 Tricks to Stop Anxiety Fast

Pranayama aside, why the 4–4, if later he advocates 4–8? It makes no sense.

The first video being longer, and more into pretending to provide some scientific explanations, I found myself commenting on it:

First, it’s not about balancing the CO2 vs O2, but making sure the blood’s pH doesn’t increase too much. You didn’t fully explain the Bohr effect. The increase in CO2 over a certain level is necessary in order to decrease the blood’s pH through the production of H2CO3, so that the oxygen from the hemoglobin could be released. It’s a question of acidity!

Note that this only works with CO2. The carbon monoxide (CO) is competing with the O2 for binding with hemoglobin, and it’s about 200 times more effective in doing that. You definitely don’t want CO, as it will deplete you of O2. But CO2 has a very definite role, and a positive one.

Secondly, the “simpler” device you showed us is the POWERbreathe Plus breathing trainer, which is a crucial IMT (Inspiratory Muscle Training) device I highly recommend to all. Yours is a Medium Resistance (blue) one; I’m using a Light Resistance (green) one, and there’s also a a Heavy Resistance (red) one. Each of them is highly adjustable, and people should start with the lowest level of resistance. Also, with such devices, one can exhale through the mouth, as the resistance is opposed only on inspiration, not on expiration.

It’s funny how you’re owning such a device, yet you’re not advertising it. OK, they didn’t pay you for that. They didn’t pay me either, but I’m making a public service here by recommending the POWERbreathe Plus IMT devices: people should educate themselves about such devices, as they can help them a lot!

His answer:

Nobody said anything about carbon monoxide, bizarre comment. Zero people advocate breathing carbon monoxide. I don’t like the POWERBreathe, it’s nearly impossible to clean and inhaling bacteria that grows from mouth contact is really bad. Cheaper / small ones can be boiled. Couldn’t care less if they pay me, I don’t sell sponsorships.

I replied with my usual diplomacy:

Sorry for being blunt, but are you retarded? I just stressed on how much different CO2 and CO are! Most people would assume that both are equally dangerous, that’s all. I tried to educate. Sorry if you, as an American, have the tendency of being dumb.

So, beside the fact that he’s so retarded that he cannot see why I mentioned the CO, he’s also exhibiting another weirdness: during the video, although he clearly also shows a POWERBreathe device, he prefers to use a different breathing exerciser, using balls:

There are literally thousands of Chinese offers for such devices. They’re cheap. Some are using the term spirometer, but such cheap plastic contraptions aren’t properly calibrated and they cannot be used to measure anything about your lungs. They are nonetheless useful to help you with resistance breathing exercises.

What I prefer, as I mentioned in the comment, is a genuine POWERBreathe device:

Unfortunately, the list prices are horrendous: £49.99 for any Plus device is just crazy! I was able to find one of them (the LR green one) for less than €30, on Amazon.de. Note that they don’t always stick to the original color coding (green for light resistance, blue for medium resistance, red for heavy resistance), and that, to the original range of Inspiratory Muscle Training devices, they added a range of Expiratory Muscle Training devices (the middle EX1 one in the picture above), which are useful to musicians and athletes.

There are many other types of helpers for breathing exercises, some unsanely expensive (but well-built), others extremely cheap (but really cheapo).

Takeaways

Breathing is important. Diaphragmatic breathing is what everyone should be doing. It improves your health, it decreases your stress, it strengthens your lungs and your heart, it brings more oxygen to your brains, it improves your sleep.

Especially for people with pulmonary or heart conditions, resistance breathing devices are recommended to be used daily (30 breaths, twice a day), with the resistance gradually increased in time. Normally, the resistance should be opposed on inspiration only, but sometimes the expiratory muscles might benefit from being trained too (using a different device).

Breathing slowly is also a key point in fighting the stress and the high blood pressure. Holding your breath while doing so is a welcome addition, should you be able to do it. With or without it, I identified here several approaches:

- 4–6 breathing

- 4–7–8 breathing

- 4–4 breathing

- 4–8 breathing

- Pranayama with Jalandhara Bandha (chin locking), which is a 4–4–4 breathing triangle in the very basic variant showed above

To each one, whatever fits them, but I’d skip the 4–7–8 one and replace it with Pranayama. Otherwise, 4–6 or 4–8 are easier to perform.

LATE EDIT: Michael Mosley suggests an easier to perform 4–2–4 breathing exercise.

Extra tip

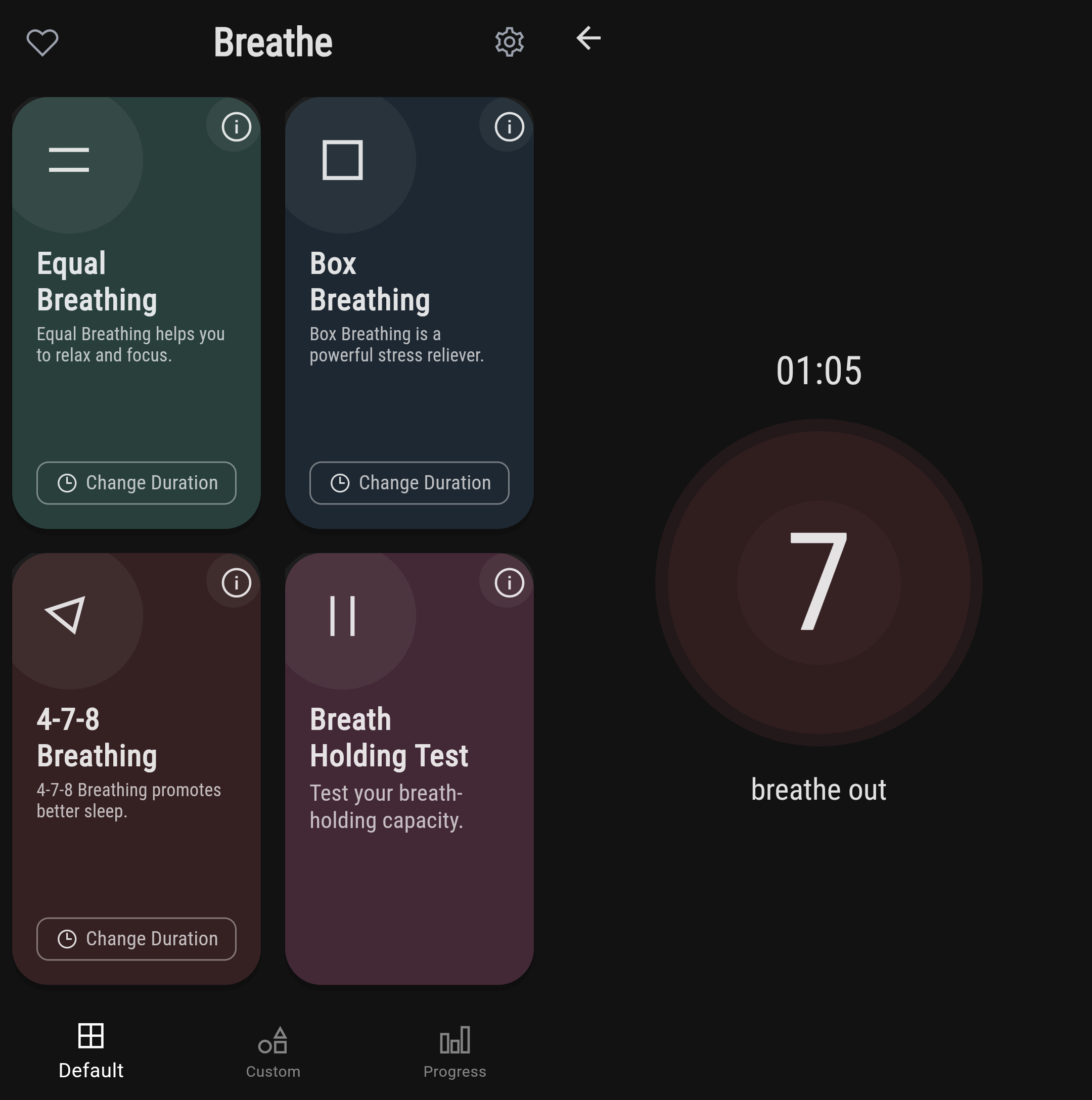

I just discovered an app that helps you observe the timings of such breathing patterns, and also to count them. Breathe: relax & focus, by Havabee. Also on iOS (listed as being by Mustafa Bhatkar).

Breathe has 3 default breathing exercises, but it allows you to create your own custom breathing patterns:

- Equal Breathing: 4-4. Defaults to 7 cycles (56s).

- Box Breathing: 4-4-4-4 (an extra 4-second hold after breathing out). Defaults to 4 cycles (1m 4s).

- 4-7-8 Breathing: defaults to 4 cycles (1m 16s).

NEW TOPIC: Sleeping well without a CPAP device

A couple of weeks ago, although I got enough sleep on Saturday night, I woke up very tired. More tired than I was when I went to bed! Coincidentally, I came across this article discussed on Hacker News: BBC Future: Why do some people feel tired all the time?

The condition is so frequent that the National Health Service even has its own acronym for it: TATT (Tired All The Time).

…

Syncing sleep with our natural circadian rhythms – the brain’s 24-hour internal clock that regulates the cycle of alertness and sleepiness – gives rise to the best-quality rest. … “Among other things, if you get that same eight hours of sleep, but not during the regular circadian period, you get almost no REM sleep and you’re not really reaping the benefits,” says Blum, referring to the fourth and final stage of our sleep cycle that’s characterised by rapid eye movements, where we typically dream, strengthen neural connections, and process emotions from the day. Too little or dysregulated REM sleep has been linked with depression, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and other cognitive issues.

…

Blood tests can sometimes be useful in pinpointing thyroid disorders or an imbalance of oestrogen and other hormones – conditions that are frequently linked with feelings of fatigue, especially in women.Tests can also reveal if you’re lacking certain nutrients like vitamin B12, folate, and D; or minerals such as iron and magnesium. “Nutrient deficiency plays a substantial role in contributing to fatigue,” says Geir Bjørklund, who founded the Norwegian nonprofit Council for Nutritional and Environmental Medicine.

…

Stress, in particular, is a big contributor to fatigue. … When we’re stressed, our bodies produce a hormone called cortisol, which in turn raises our body temperature and heart rate to gear us up to face a threat. Cortisol levels fluctuate naturally throughout the day, but when they remain elevated, it’s harder to fall asleep and stay asleep. It’s that “tired but wired” feeling, says Whittemore.Another really common cause of fatigue in otherwise healthy people is sleep disorders or breathing issues, says Blum.

This includes snoring, which occurs when one’s airway is partially or fully blocked. “All snoring is abnormal, and may be a sign of sleep apnoea,” he says, referring to the disorder that causes some sleepers to stop and start breathing repeatedly throughout the night.

All this can disrupt natural sleep patterns and make deep sleep elusive, says Blum. “So people get that seven to nine hours of sleep, but it’s insufficient quality.”

From the comments on Hacker News:

• For me it was sleep apnea. It was undiagnosed and I have lived most of my life basically exhausted.

Once I was diagnosed, thanks to a CPAP recall/shortage during the pandemic I couldn’t get a CPAP machine so used a custom fit oral appliance which took a few days to get used to, but once I did I woke up one day, having done nothing very different from any other day, feeling fresher than I can ever remember feeling.It was fascinating to realize that I had basically lived my entire adult life of over 2 decades in a half asleep stupor.

• It can be incredibly hard to get a diagnosis. Even when you are shown to have it, you can find out that insurance uses an entirely different metric and, therefore, will refuse to pay.

• Did you have any issues with the device when you first got it? I’ve been using a CPAP machine for a while, but it took me literally years before I could sleep through an entire night with it on. I’ve been thinking of either having surgery or going the oral appliance route this year.

• For me the trick was a full face mask (Dreamwear, where the hose comes out the top of your head) and a heated hose.

I was initially resistant to the full mask, thinking it would feel more restrictive than the nose-only, but distributing the pressure over a wider area ended up feeling a lot more comfortable.

Similarly with the heated hose, my initial thought was that it would feel like breathing hot air all night. The the actual effect is that it keeps the added humidity from condensing out out of the air and gurgling in the tube.

The problem is that those CPAP ratshits, beyond the outrageous price (of the machine, not of the mask itself), are impossible to wear. They’re stumpy as if they were astronaut helmets from the 1960s: how the hell can you not make something more sleek in the 21st century? Gazillions of somnologists theorize endlessly, but the solutions they recommend are instruments of torture!

Besides, the principle is strange: continuous positive airway pressure. It’s always blowing air into your mouth, and by the time you get used to it, you feel like it’s trying to kill you, to suffocate you! All they can have “smart” is to blow initially more slowly, until you fall asleep, and increase the pressure only when you tend to snore. But is it rocket science to design something that adapts to your rhythm and performs a full, push-pull breathing cycle? WTF, it’s 2024, not 1954!

Then there are various jaw devices, which IMO are but other instruments of torture.

And then, various cheap tricks of which I’ve tried some years ago, with no real results.

Also, recently I found out about these shitty micro-CPAP devices; there are thousands of almost identical Chinese clones:

Apparently, they would be useless: they don’t make enough pressure, in fact almost not at all!

Browsing on YT, I came across the channel of a licensed UK otolaryngologist, Vik Veer, ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgeon, Royal National ENT Hospital, Queen’s King George’s Hospital, London. He, too, tested some such useless toy: A Sleep Surgeon Tests a MicroCPAP / Airing device. Other of his tests include: Do chin straps and mouth tape cure snoring? | Cheap Devices that Reduce Sleep Apnoea by 53%: A Review of Tongue Retaining Devices | A sleep doctor tries to use snoring mouth guards / Mandibular Advancement Devices. A viewer’s comment:

@tylerhuntley9454: I was diagnosed with moderate sleep obstructive apnea about 5 months ago. I tried CPAP for a month & honestly just wanted to die. Went from 8 hours of “sleep” to 3 hours max per night after trying 5 different masks. I dumped my sleep clinic & went to the dentist to get a 3D printed custom MAD here in Australia. Best $2000 I’ve ever spent. I sleep the whole night through and no longer wake up feeling like a cancer patient every morning.

I’m currently at 70% titration and only had jaw pain the first night (did not expect such a quick adjustment). I’m still tired, but no where near the extent I was, and even my partner notices my peppier demeanour. Only issue is dry mouth if I’ve been sleeping on my back too much without having the sleep apnea pillow supporting my neck properly. But I think that’s worsened by my neck posture, which my chiro can fix when I have the money to see him regularly. TDLR: keep trying to fix your sleep apnea, and make sure you are taking as holistic of an approach as possible. It’ll change your life!

Other tests and videos by the same guy: iNAP: A New Treatment for Sleep Apnoea! A true alternative to CPAP? | A Review of the Latest Snoring Device: ZEUS | Can’t sleep with CPAP? Watch this! | How I think sleep apnoea should be treated | Unblock your Nose WITHOUT Surgery – A Review of Nasal Dilators | Throat Exercises for Snoring and Sleep Apnoea (myofunctional therapy) | Five Exercises for Snoring and Sleep Apnoea (Updated) | Will losing weight cure my snoring? The answer may surprise you (it’s a vicious circle).

Sleep apnoea could and should be treated in many ways, but CPAP = torture, full stop.

Oh, and I ran over another type of a scam device:

It’s supposed to give you a small electric shock when hearing your snoring, but, for a similar enough device (I just couldn’t find any honest feedback for a device looking exactly as depicted above), people complained that, “it zapped me, I have two bruise burn marks from it”; “It shocked me out of my sleep”; “I’m a victim of this scam product, after 1st night got 2 blisters on my neck, the skin is kind of burnt and keep on itchy for days before recovered.”

Well, here goes the myth of the cheap, miraculous device that would eliminate your snoring.

But then… I was struck by the idea of using the IMT breathing muscle exerciser I mentioned in this post! In theory, the purpose of these inspiratory muscle training (IMT) devices would be different:

IMT devices provide resistance during inhalation, requiring the inspiratory muscles (such as the diaphragm and intercostal muscles) to work harder. This resistance helps to strengthen these muscles over time. For individuals with respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, IMT can help reduce breathlessness by enhancing the efficiency of the respiratory muscles. This improved respiratory function also helps during endurance sports or high-intensity workouts.

But shortness of breath doesn’t just come from asthma, it can also be a heart-related issue, even if not a medical condition, but in overweight people like us, the heart works harder. And there’s a theory that “breath education” can not only help with better oxygenation, but also help the heart somewhat, including hypertension.

On the sleep apnea side, I spotted a couple of studies saying that IMT devices should help:

● Effect of inspirational muscle training in patients with obstructive sleep apnea

Conclusion: Preliminaries data showed that IMT with POWERbreathe® medic can reduce daytime hypersonness signs, improve the quality of sleep impacting on apneia and hypopneia index of polysomnography and may become a new alternative treatment for patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Conclusions: The results are consistent with our previously published findings in normotensive adults but further indicate that IMT can modulate blood pressure and plasma catecholamines in subjects with ongoing nighttime apnea and hypoxemia. Accordingly, we suggest IMT offers a low cost, nonpharmacologic means of improving sleep and blood pressure in patients who are intolerant of CPAP.

5. Conclusions

IMT improves sleepiness, sleep quality and inspiratory strength in patients with OSA. Future studies are recommended in order to explore the benefits of EMT in OSA patients.

Abstract:

Methods: Five sedentary OSA patients participated in this feasibility study (three men, mean age = 61.6 years, SD = 10.2). Using a digital POWERbreathe K4 or K5 device, participants performed 30 daily inhalations against a resistance set at a percentage of maximum, recalculated weekly. Participants were willing to perform one but not two daily practice sessions. Intervention parameters from common IMT protocols were adapted according to ability and subjective feedback. Some were unable to perform the typically used 75% of maximum inspiratory resistance so we lowered the target to 65%. The technique required some practice; therefore, we introduced a practice week with a 50% target. After an initial 8 weeks, the intervention was open-ended and training continued until all participants demonstrated at least one plateau of inspiratory strength (2 weeks without strength gain). Weekly email and phone reminders ensured that participants completed all daily sessions and logged data in their online surveys. Weekly measures of inspiratory resistance, strength, volume, and flow were recorded.

Results: Participants successfully completed the practice and subsequent 65% IMT resistance targets daily for 13 weeks. Inspiratory strength gains showed plateaus in all subjects by the end of 10 weeks of training, suggesting 12 weeks plus practice would be sufficient to achieve and capture maximum gains. Participants reported no adverse effects.

Conclusion: We developed and tested a 13-week IMT protocol in a small group of sedentary, untreated OSA patients. Relative to other IMT protocols, we successfully implemented reduced performance requirements, a practice week, and an extended timeframe. This feasibility study provides the basis for a protocol for clinical trials on IMT in OSA.

Introduction

Over 10% of the population suffers from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a disorder characterized by repeated pauses in breathing during sleep due to collapsing of the upper airway (Peppard et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2014). The condition is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease including hypertension and cardiovascular disease (Monahan et al., 2009; Peppard et al., 2013; Javaheri et al., 2017; Whelton et al., 2018). Nightly use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), the standard treatment for OSA, resolves the breathing disruptions and improves some of the symptoms, but shows mixed results for reducing blood pressure (BP) (Barbé et al., 2012; McEvoy et al., 2016; Whelton et al., 2018). Furthermore, CPAP adherence is often low, as patients experience it as intrusive and difficult to wear throughout the night. In some patients, weight loss and physical exercise improve daytime symptoms and breathing during sleep, but as with other chronic conditions, more often than not, stable long-term health behavior change in OSA is not achieved (Aiello et al., 2016; Vranish and Bailey, 2016; Souza et al., 2018; Carneiro-Barrera et al., 2019). Consequently, there remains a need for complementary or alternative interventions for treating OSA and its comorbidities.

One potentially beneficial intervention for people with OSA is inspiratory muscle training (IMT). IMT is the practice of strengthening respiratory muscles involved in inhalations (Larson et al., 1988). Simplistically, OSA arises from a failure of breathing, therefore training breathing may improve symptoms. More specifically, since OSA involves the collapse of the upper airways with inspiration during sleep, IMT may reduce the number and/or severity of apneas by improving upper airway muscle tone (How et al., 2007). In addition, IMT may also improve cardiovascular symptoms, since studies in normotensive adults and patients with OSA found significant reductions in BP with IMT, and improved functional capacity in people with heart failure (Ferreira et al., 2013; Vranish and Bailey, 2015, 2016; Posser et al., 2016; DeLucia et al., 2018; Fernandez-Rubio et al., 2020; Ramos-Barrera et al., 2020). The mechanism of IMT effects on cardiovascular function is unknown, but may be due to either associations between respiratory and cardiovascular activity, or due to potential positive IMT-related effects on stress (Grossman et al., 2001; HajGhanbari et al., 2013; de Abreu et al., 2017; Fernandez-Rubio et al., 2020). Regardless of the mechanism, the evidence suggests that IMT has the potential to improve both breathing and cardiovascular symptoms in OSA.

Well, that bit at the end about protocol is a bit superfluous. There is more literature on how to use IMT devices. If you can’t medically measure that maximum resistance they mention, the manufacturer’s recommended protocol is, simply put, to start from the “lightest” device (the green one), from the lowest step (0), and do 30 breaths twice a day. If you have no trouble doing a set of 30 without a break, next time you increase the level (from 0 to 10, but advance by quarter turns, which are quarter levels). When you “finish” a device, you switch to a medium-strength one, which you start at 0, then a high-strength one.

Unfortunately, the results come slowly over time. Probably months. And I don’t know what is noticed first: that you can run up stairs without panting, or that you snore less?

I started breathing exercises yesterday. I keep the device handy, but I lack the required discipline!

Added an app that helps with observing such breathing patterns, and a section on POWERbreathe device to help with snoring and sleep apnea, after having dismissed other helpers.

«New York Times names Smart Nora ($359) “Best Anti-Snoring Device” for a fourth year in a row.» They surely did: I Tried 6 Anti-Snoring Devices. The Smart Nora Worked Best.