SPECIAL: Trust your gut, but revise your subjunctive—and beware of dictionaries!

In my previous post, I ended a sentence like this: “the first documentary I’m going to suggest you watch.” Later, I suddenly asked myself: why did I use this construct? It just came to me this way, but shouldn’t it have read, “I’m going to suggest you to watch”?

No, it should not! But why? Even as a non-native speaker of English, sometimes the “gut feeling” dictates, because I am not a walking grammar book.

1. It’s all about the subjunctive! | 2. Interlude: why Merriam-Webster sucks! | 3. Intermezzo italo-francese | 3.1 Why French dictionaries suck big time | 3.2 Large common monolingual Italian dictionaries | 3.3. The Treccani case | 4. Back to using “to suggest” | 5. Merriam-Webster censors!

It’s all about the subjunctive!

Most people associate the word subjunctive in English with the “I wish I were…” type of sentence, because they’re told that’s the main surviving use of the past subjunctive in modern English. And they don’t use it anyway, so they say, “I wish I was…,” especially in the States.

Even usage notes in dictionaries insist that the subjunctive is mostly dead in English.

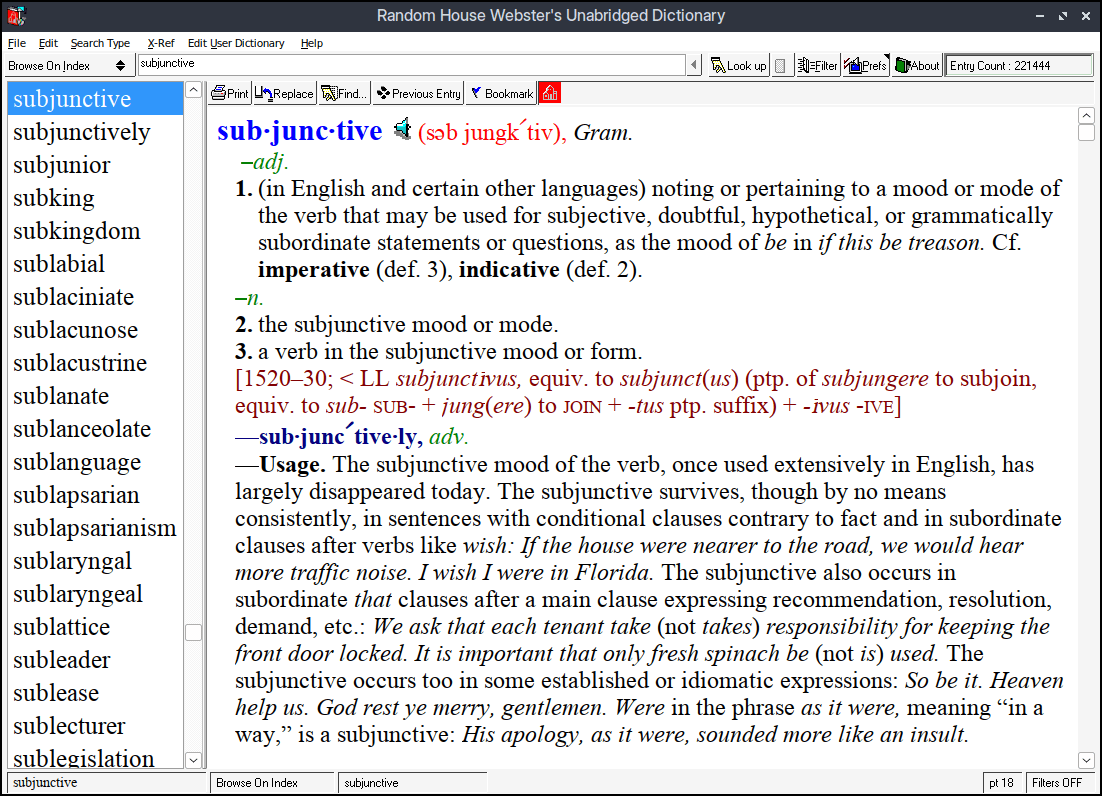

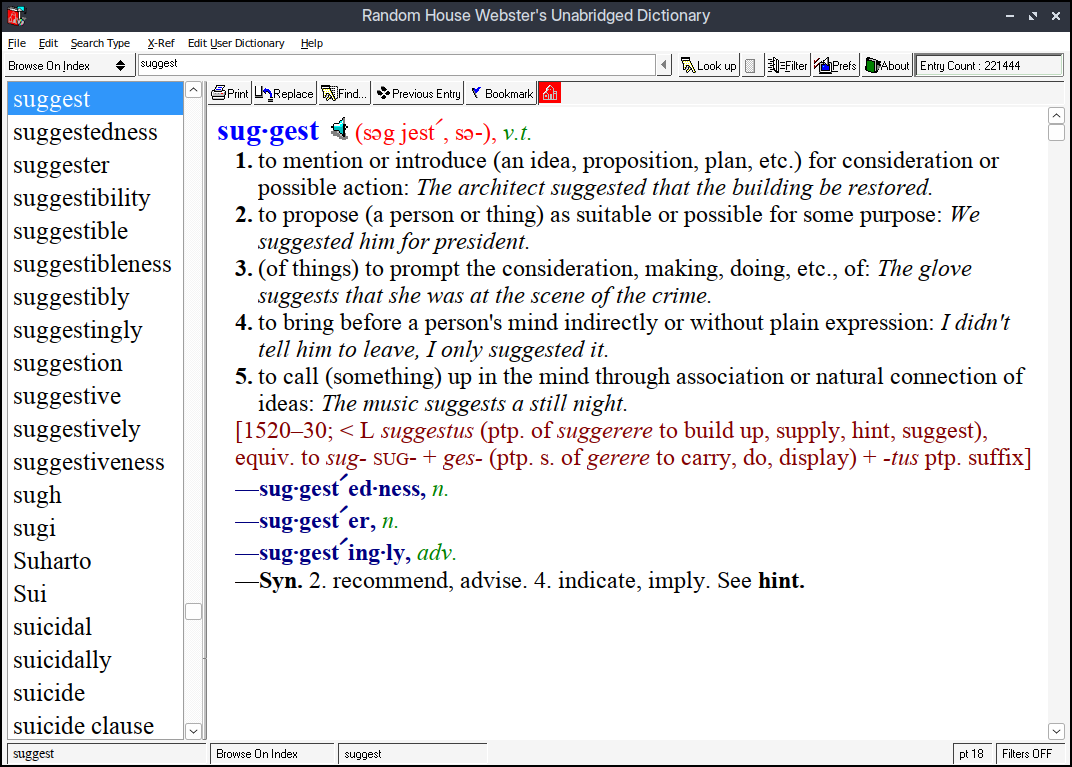

Because I still believe that Random House’s now defunct major dictionaries—meaning the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (first edition 1966, second edition 1987, revised and updated in 1991, 1993, 1997, and reprinted in 1999, 2001, and with a new green cover in 2002 and 2005), aka RHWUD, and the Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (first published in 1947 as the American College Dictionary, then in 1968 as Random House Dictionary of the English Language, College Edition, later renamed Random House College Dictionary, and since 1991 bearing the name Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, updated annually in print until its last “red edition” in 2000—an edition that I own—then reprinted without updates until 2005, when it had a blue cover), aka RHWCD—had the best and clearest definitions, I’ll resort to the definition of “subjunctive” from the only surviving form of RHWUD. Bertelsmann purchased Random House in 1998, then closed down the dictionary division in January 2002, but for some years the database survived online as part of Dictionary.com. Somewhere around 2020-2021, the licensed content moved to CollinsDictionary.com.

UPDATE: The last “red edition” in print of the Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (RHWCD), which I own (the normal, non-deluxe version), was this one:

2001 Second Revised and Updated Random House Edition

April 2001

©2001 by Random House, Inc.

ISBN: 0-375-42560-8

ISBN: 0-375-42561-6 (Deluxe Edition)

So here’s subjunctive. Scroll down past the definition from the Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (a dictionary made by retards, or maybe for retards; when definitions in simple words are desired, prefer any of the following: Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners). Scroll down further past the definition “in British English” from the Collins English Dictionary (which should have been the only one at this URL), and past the first result “in American English” from the Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 5th Digital Edition. You’ll then find a 2nd result “in American English”: “Most material © 2005, 1997, 1991 by Penguin Random House LLC. Modified entries © 2019 by Penguin Random House LLC and HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.” That’s from the RHWUD, slightly updated:

subjunctive (səbˈdʒʌŋktɪv)

adjective

- (in English and certain other languages) noting or pertaining to a mood or mode of the verb that may be used for subjective, doubtful, hypothetical, or grammatically subordinate statements or questions, as the mood of be in if this be treason.

Compare imperative (sense 3), indicative (sense 2)noun

- the subjunctive mood or mode

- a verb in the subjunctive mood or form

USAGE The subjunctive mood of the verb, once used extensively in English, has largely disappeared today. The subjunctive survives, though by no means consistently, in sentences with conditional clauses contrary to fact and in subordinate clauses after verbs like wish: If the house were nearer to the road, we would hear more traffic noise. I wish I were in Florida. The subjunctive also occurs in subordinate that clauses after a main clause expressing recommendation, resolution, demand, etc.: We ask that each tenant take (not takes) responsibility for keeping the front door locked. It is important that only fresh spinach be (not is) used. The subjunctive occurs too in some established or idiomatic expressions: So be it. Heaven help us. God rest ye merry, gentlemen. Were in the phrase as it were, meaning “in a way,” is a subjunctive: His apology, as it were, sounded more like an insult.

Compare to the last standalone edition:

So you have shown, more succinctly than in a grammar book, several forms of subjunctive:

- Past subjunctive: “I wish I were…” / “I wish it were…” / “If I were…” / “If it were…” (not “was”).

- Present subjunctive with “that”: “We ask that each tenant take (not takes) responsibility…” / “It is important that only fresh spinach be (not is) used.” (In AmEn the use of “that” is optional.)

- Idioms: “So be it.” “Heaven help us.”

- “as it were…” to mean “in a way,” “so to speak,” or “in a manner of speaking.”

We’ll come to some of them later. The funny thing is that English speakers dread the subjunctive in Romance languages, where it’s extremely popular (Italian, French, Spanish), yet this mood is present in English in even more confusing ways than they thought!

Interlude: why Merriam-Webster sucks!

Since I expressed my preference for the definitions from a dead dictionary, I need to explain my choice. Of course, I understand that many Brits prefer the definitions from Collins (I did the same in the 1990s), from ODE (the one-volume Oxford, not to be confused with OED), maybe from Chambers if they like concision (I still cherish the 13th edition, 2014), and, from the American publishers, the AHD. Unfortunately, even as I’ve been taught BrEn in school, I’m now into AmEn (I cringe when I read or hear “lorry” or “crisps,” and “metre,” “centre,” and “theatre” sound French to me). But in AmEn, the only living dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s! By “living,” I mean that it’s updated at least in its digital editions, that it has apps, and that it can be consulted online.

Unfortunately, Merriam-Webster has the worst definitions that could be found in an American dictionary!

But first, let’s talk about some editorial choices specific to M-W.

Some dictionaries give the definitions from the oldest to the most recent meaning; some others start with the most common meaning, which sometimes isn’t the oldest one. To the point:

- Merriam-Webster is the only American dictionary (in its Unabridged, Collegiate, and online or app editions) that orders definitions chronologically, by historical development (oldest first). In Britain, only the huge Oxford English Dictionary (OED) does the same, whereas the one-volume Oxford Dictionary of English (ODE) does not; Chambers is the odd one that also lists the oldest meanings first, because it’s a concise dictionary known for including archaic, dialectal, and eccentric words or meanings that other dictionaries omit. I use it to read 19th-century or older British fiction.

- The Random House dictionaries (RHWUD and RHWCD), the American Heritage Dictionary (AHD), as well as most contemporary dictionaries on planet Earth, follow the most common usage approach: definitions are typically arranged by frequency or relevance in modern contexts. While the etymology is given at the end of the entry, a practical dictionary is supposed to present the most common sense upfront, to minimize the time spent, statistically, by a user who tries to find a definition.

Then, M-W also has a couple of idiosyncrasies: they separate meanings with a colon, not a semicolon, and for some meanings, they just send you to another word in CAPITALS that has a meaning supposedly synonymous with the respective meaning of the current word. This can be annoying and confusing, and I’ll give you some quick examples.

anger, noun

2 : a threatening or violent appearance or state : RAGE sense 2spruce, adjective

: neat or smart in appearance : TRIM

But trim, as an adjective, has four meanings in the same dictionary! Why isn’t the sense number specified, like they did for anger?

fear, noun

1 a : an unpleasant often strong emotion caused by anticipation or awareness of danger

b (1) : an instance of this emotion

(2) : a state marked by this emotion

2 : anxious concern : SOLICITUDE

3 : profound reverence and awe especially toward God

4 : reason for alarm : DANGER

Sorry, but “solicitude” and “danger” have several meanings each. And nobody would use “solicitude” instead of “fear”! Also, “danger” isn’t quite synonymous with “reason for alarm”!

Should I add that the typical punctuation rules ask for two commas that aren’t there? Like so: “an unpleasant, often strong emotion” and “profound reverence and awe, especially toward God.” And this is the number one dictionary in America!

Compare to Random House (I skipped the verbal values, as we’re comparing the definitions for the noun):

fear, noun

- a distressing emotion aroused by impending danger, evil, pain, etc., whether the threat is real or imagined; the feeling or condition of being afraid.

- a specific instance of or propensity for such a feeling: an abnormal fear of heights.

- concern or anxiety; solicitude: a fear for someone’s safety.

- reverential awe, esp. toward God.

- that which causes a feeling of being afraid; that of which a person is afraid: Cancer is a common fear.

SYNONYMS 1. apprehension, consternation, dismay, terror, fright, panic, horror, trepidation. FEAR, ALARM, DREAD all imply a painful emotion experienced when one is confronted by threatening danger or evil. ALARM implies an agitation of the feelings caused by awakening to imminent danger; it names a feeling of fright or panic: He started up in alarm. FEAR and DREAD usually refer more to a condition or state than to an event. FEAR is often applied to an attitude toward something, which, when experienced, will cause the sensation of fright: fear of falling. DREAD suggests anticipation of something, usually a particular event, which, when experienced, will be disagreeable rather than frightening: She lives in dread of losing her money. The same is often true of FEAR, when used in a negative statement: She has no fear she’ll lose her money.

Now tell me again why RH died, and M-W survived!

OK, I can find some grounds for that:

- M-W is the default dictionary for many US schools, publishers, and government agencies.

- It’s often bundled with software and platforms (Kindle).

- M-W has several “extras” online: WOTD, quizzes, word games, slang (6-7, anyone?), trending words, etc. They have apps. Their FB and X accounts are helpful, too.

- Random House’s dictionary division has been mismanaged by Bertelsmann, who didn’t think of offering an online version or apps.

One more comparison, this time for a meaning of to roast that originates with the Friars Club in New York (1940s) but became widespread once it was popularized by Comedy Central.

M-W:

roast, verb

…

4: to honor (a person) at a roast (see ROAST entry 2 sense 5)roast, noun

…

5 : a banquet honoring a person who is subjected to humorous tongue-in-cheek ridicule by friends

a celebrity roast

This literally gives “to honor (a person) at a banquet honoring a person…”

Random House:

roast, v.t.

…

9. to honor with or subject to a roast: Friends roasted the star at a charity dinner.–n.

…

17. a facetious ceremonial tribute, usually concluding a banquet, in which the guest of honor is both praised and good-naturedly insulted in a succession of speeches by friends and acquaintances.

Some quirks:

- M-W is owned by Encyclopædia Britannica, but it’s M-W that keeps Britannica alive!

- Strangely enough, M-W’s compact, mass-market editions, sometimes bundled with a thesaurus, have clearer definitions, but a limited entry count, as they’re sanitized for K-12.

Other times, though, M-W gives full definitions, whereas Random House uses pointers.

M-W:

solifluction : the slow creeping of saturated fragmental material (such as soil) down a slope that usually occurs in regions of perennial frost.

Random House:

solifluction: (Geology) creep (sense 17a)

creep: 17. (Geology) a. the gradual movement downhill of loose soil, rock, gravel, etc.; solifluction.

And yet, “creeping down a slope” (M-W) is less understandable than “gradual movement downhill.”

More criticism now.

M-W’s online edition, as well as the one available in the apps, is derived from their Collegiate Dictionary, with a few differences. But let’s break the news first: For the first time in over twenty years (see also here), and only the twelfth time ever, Merriam-Webster releases a new edition of its Collegiate Dictionary, the 12th, on Nov. 18, 2025, in the States, and on Jan. 5, 2026, globally!

Comparing the Collegiate, 12th Ed., to the Collegiate, 11th Ed., and to the online/app editions:

- The 12th edition has over 5,000 new words and 1,000 new phrases and idioms in addition to the 11th edition, which is very little for 22 years!

- The 12th edition has more than 20,000 additional usage examples, but the online edition and the apps have many more examples.

- The 12th edition lacks some slang or disparaging meanings!

- Some words present in the 12th editions are missing from the online and apps editions!

This is such a mess. OK, the examples that aren’t usage examples proper but random citations (not from famous authors, mind you) are mostly garbage, but still.

- Take beta-amyloid (online) and compare it to the printed 12th edition: 3 citations versus 1 citation.

- Take beta (online) and compare it to the same printed page. For the noun, the sense “2. b. slang, disparaging : a timid, weak, or submissive person,” together with a citation from Dieter Kurtenbach, is missing completely from the printed edition, and the same applies to the adjective, the sense “2. slang, disparaging : socially submissive or subordinate : having the character, qualities, or status of a beta: a beta male“! WTF is this?!

- On the other hand, from the 4 new words mentioned in the press release, cold brew (short for cold brew coffee) and farm-to-table are not present in the apps (not updated since July) and have been added in the online version a few days ago, whereas rizz (who the fuck selected the citations, including one by “@ArtsyVRC, on X, formerly Twitter”?) and dad bod are also in the apps.

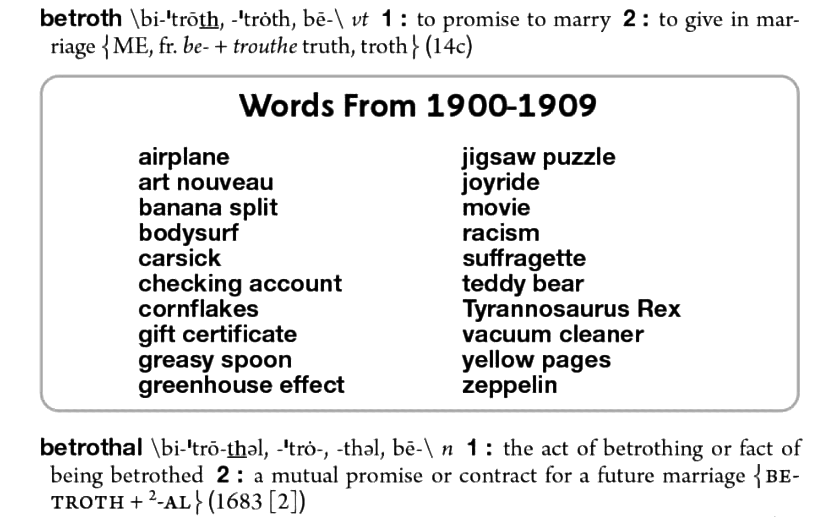

If they counted on the extra contents added to the print edition, there isn’t anything spectacular, and some extras are particularly dumb. Why are these 20 words from 1900-1909 between “betroth” and “betrothal,” and where to look for words from 1910-1919?!

Strange case, that of “greenhouse effect”: M-W says its first known use was in 1907, RH says it started being used in 1935-1940, and no other dictionary gives any date. Indeed, John Henry Poynting explicitly used “greenhouse effect” in 1907 in the meteorological sense, after Nils Gustaf Ekholm wrote in 1901 that “the atmosphere may act like the glass of a green-house” (page 19). But when the phrase started being really used, that’s hard to tell.

When coming from Google, M-W’s online edition sometimes grants you free access to the definition of some word that’s only in the Unabridged edition. But no, there’s no app for that. And Unabridged is only available by subscription: $4.95/month or $49.50/year. Are they kidding me?!

Their Unabridged is as good as dead, and so is Britannica. The same could be said about the French Le Grand Robert (€6.99/month or €69.90/year). Close to nobody’s using it. The subscription model only works if it’s cheap enough because, for fuck’s sake, it’s a dictionary, not Adobe Photoshop or Illustrator! But the French are outrageous. For Le Petit Robert de la langue française with yearly updates, the subscription is €4.99/month or €49.90/year (the free online version lacks a lot of new words). Compare this to the Italian Lo Zingarelli, also updated annually, which costs €13.10/year, and it’s much more comprehensive than Le Petit Robert. The other Italian dictionary that’s continuously updated, Il Nuovo Devoto-Oli Digitale, costs €16.99/year. And the Italians include in the price apps to supplement the browser access.

But Merriam-Webster disappoints in many other ways.

Very often, the Android app falls behind the online one, thus lacking newer words. Or there are some other unexplained aspects. Right now, M-W Premium says, “Updated on Nov 15, 2025,” but on my phone, “Last updated 5 Jul 2025” (both read version 5.5.5), despite my phone having the latest Android 16. For whom is the Nov 15 update? Then, the Premium version is not only ad-free, but it claims to include “Premium Content: over 1000 graphical illustrations, and over 15,000 additional entries covering people and places.” Yeah, sure. How about missing entries? And I’m not talking of recent words, but of old entries that can be found online, but not in the fucked-up app! Take zugzwang. Every half-decent dictionary has it. But not Merriam-Webster’s app, either free or premium! The retarded developers have broken the database. I suppose the entry was there at some point, but I couldn’t tell.

Should I add that this app used to cost $5.99/€5.99 (USD doesn’t include the sales tax; EUR is VAT-inclusive) at some point, and even €2.26 when I purchased it in April 2026, but now it’s $7.99/€7.99 (€8.49 in France, because, err, France)? You get many more words online, for free, and with zero ads if you’re using uBlock Origin! The app is simply a scam.

Some technical details on how they count the words. The number of entries, not the number of definitions, like many dictionary makers do to impress!

Regarding the ~300k word forms, they include all the alternative spellings, idioms (phrases) that are indexed (so they should result in a search), plurals, and conjugations. For instance, the entry #8, for the headword abide, has 10 word forms that are counted: abide, abide by, abided, abided by, abider, abiders, abides, abides by, abiding. Entry #10 has 3 word forms: abstention, abstentions, abstentious. Note that abstentious doesn’t have a separate entry because it’s not explained; it’s merely listed.

Version 5.4.1 (June 2023):

- TABLE all_words:

- rows (=word forms): 327,824

- headwords: 126,374

- TABLE definitions:

- rows (=entries): 128,481, of which:

- dictionary entries: 85,084

- thesaurus entries: 72,290

- dictionary entries that have a thesaurus counterpart: 28,883

The last two values don’t make sense! I’m pretty sure most of the thesaurus entries in that table are bogus. So the number of rows in the same table is also inflated with junk.

Version 5.5.3 (June 2024):

- TABLE all_words:

- rows (=word forms): 329,025 (1200 more!)

- headwords: 126,601

- TABLE definitions:

- rows (=entries): 128,697, of which:

- dictionary entries: 85,302

- thesaurus entries: 72,290

- dictionary entries that have a thesaurus counterpart: 28,895

What didn’t make sense still doesn’t.

Version 5.5.5 (May 2025):

- TABLE all_words:

- rows (=word forms): 265,877 (much fewer word forms!), of which:

- headwords: 99,148 (they must have made a clean-up!?)

- TABLE definitions:

- rows (=entries): 142,540 (quite an improvement), of which:

- dictionary entries: 99,148 (this time, it makes sense)

- thesaurus entries: 72,289

- dictionary entries that have a thesaurus counterpart: 28,897

With all the cleanup, the only thing that makes sense is that the number of headwords is the same as the number of dictionary entries: 99,148. Therefore, I suppose that this is the relevant number in the previous versions, too.

Either way, it’s merely a joke. How many entries beyond zugzwang aren’t there, despite being in the online edition! Just use a browser!

Speaking of online English dictionaries, AHD is now under HarperCollins, so it’s as good as dead and not going to have any real update, but AHD5 can be consulted online (it’s terribly slow, though). Dictionary.com isn’t what it used to be. Collins Online Dictionary is the most complete of all, because it includes ❶ Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (retarded), ❷ Collins English Dictionary (stagnant since 2014), ❸ Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 5th Digital Edition (now under HarperCollins and almost identical to AHD5; it used to be published by Simon & Schuster in its good times), ❹ the former RHWUD listed as “Most material © 2005, 1997, 1991 by Penguin Random House LLC. Modified entries © 2019 by Penguin Random House LLC and HarperCollins Publishers Ltd,” ❺ and medium-sized bilingual dictionaries with 9 languages.

App-wise, I’d advise you to avoid the apps by MobiSystems. They suck, although the paid editions do work. All Oxford dictionaries (including the bilingual ones!) are now grouped into Oxford Dictionary & Thesaurus, which makes switching between them a bit annoying, and it makes it impossible to see relevant data (exact title, edition) for each of them.

OTOH, I do recommend the Android apps by WordWeb Software: the free WordWeb edition (with unofficial updates by Antony Lewis) and the paid Chambers Dictionary and Chambers Thesaurus. You won’t find the very last terms, obviously, except when Antony Lewis has added them to his version of WordWeb (rizz, SJW, woke, COVID-19, chatbot, ChatGPT). There are iOS counterparts, too (macOS also includes dictionaries that on mobile are only offered by MobiSystems). Windows users can install WordWeb Free (please ignore that Windows Store WordWeb app); to WordWeb Pro one can add many more paid dictionaries from Chambers, Collins, and Oxford.

Note that the Chambers Dictionary, 13th edition (2014), lacks some meanings that were present in the smaller but less concise Chambers 21st Century Dictionary (1999) that’s abandoned but available online, such as the US meaning of lame duck (M-W: “an elected official or group continuing to hold political office during the period between the election and the inauguration of a successor”; Chambers 21st: “an elected official who is in the final months of office, after a successor has been appointed”).

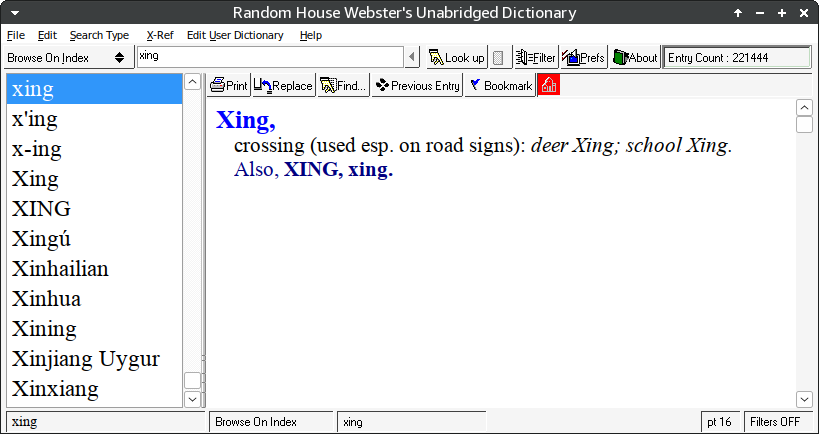

Oh, did I mention that Merriam-Webster (online and app) lacks a definition for xing?

I figured out what it means when I first met such signs in 2005 in Utah, but a decent dictionary should have it!

Instead, M-W had to have Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg, or Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg, or Lake Chaubunagungamaug, or Webster Lake, which in the app is given with the longest name not matching any of the long names shown online: Lake Chargoggagoggmanchaugggaggoggchaubunagungamaugg or Lake Chaubunagungamaug or Webster Lake.

Once again, Merriam-Webster is a joke, and it’s a shame that it was exactly this retarded dictionary that had to survive!

Speaking of words recently in top lookups on M-W.com, let’s take nuclear option, trabacolo, and barabara. (Note that trabacolo, trabascolo, trabacola, or trabacole is written trabaccolo in Italian and is synonymous with bragozzo, which exists in M-W online.)

Bits of history:

- Not in RHWUD as of 2000: nuclear option, bragozzo.

- Not in RHWCD as of 2000: nuclear option, trabacolo, barabara, bragozzo.

- Not in M-W Unabridged as of 2000: nuclear option.

- Not in M-W Collegiate as of 2000: nuclear option, trabacolo, barabara, bragozzo.

Strange thing, M-W says of nuclear option: “First Known Use: 1962,” yet it took it 40+ years to reach their dictionaries!

Just for fun, here’s a quick comparison of Random House Webster’s Pocket American Dictionary (2008) vs. Merriam-Webster’s Pocket Dictionary (2015).

Oh, I was forgetting. No mainstream dictionary includes the sarcastic use of the adverb much, except for Wiktionary (which otherwise is a huge mess), but I’m not happy with their definition:

4 (slang) Combining with an adjective or (occasionally) a noun, used in a rhetorical question to mock someone for having the specified quality.

Jamie’s always preaching about how we need to save a planet when she drives literally everywhere she goes. Like, hypocritical much?

This only covers the cases when much applies to the previous word (“Drama much?” “Obsessive much?” “Fanboy much?”), but not those when the sarcastic tag is commenting on the whole preceding phrase: “Showing off your new car, much?” “Representative democracy, much?” I hope you noticed the comma. But I believe that a comma can be added in all cases when one wants to emphasize the irony. (It’s basically verbal eye-rolling in written form.)

Dictionaries are useless. Absolutely no publishing house bothers to maintain a couple of people (say, university assistants in linguistics) who would receive input from the public and decide on a small but relevant number of definitions or entries to be added to a dictionary. Capitalism failed.

Oh, let’s amend this. Sometimes, M-W can be useful. Say you encounter this woke term invented in 2002 to designate people who don’t have all their marbles without making them sound nuts: neurodivergent (see also neurodiversity, which is not mental insanity!). Wikipedia surely elaborates a lot on such terms, even too much and annoyingly so, but the definitions from M-W are synthesizing the concept much better.

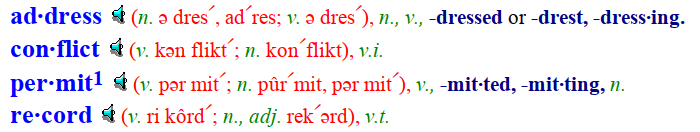

A note on syllable stress (tonic accent)

There is a pattern of words having the first syllable stressed when they function as nouns or adjectives but the second syllable stressed when they are verbs:

- address: “Adres” (noun) vs. “aDRES” (verb)

- conflict: “CONflict” (noun) vs. “conFLICT” (verb)

- permit: “PERmit” (noun) vs. “perMIT” (verb)

- record: “REcord” (noun or adjective) vs. “reCORD” (verb)

This used to be a rather strict rule, but in the last decades most dictionaries started to show “address” with the second syllable stressed in all cases. Yes, even in AmEn. This is true for Collins English Dictionary 12th Ed. (2014), the ODE 3rd Edition (2010), the NOAD 3rd Ed. (2010), and the AHD 5th Ed. (2020). But the British dictionaries have the excuse of the RP (Received Pronunciation) that irrationally prescribes the second-syllable stress for “address” as a noun, but not for “conflict”/“permit”/“record” as nouns. It is irrational because the shift in accent for “conflict”/“permit”/“record” allows for a better distinction between the noun and the verb values: “I have a PERmit” vs. “They won’t perMIT me.” This was lost for “address”!

In the States, despite people still preferring the pronunciation “Adres” instead of “aDRES” for nouns (or, at least, this was still true in 2010 in The Big Bang Theory S03E21, The Plimpton Stimulation), dictionaries now prefer “aDRES” in all cases.

M-W wrongfully mentions that there’s a choice of pronunciations for the verb, too, despite the pronunciation for the noun being the one that has evolved in time:

- address, verb: [ə-ˈdres] also [ˈa-ˌdres]

- address, noun: [ə-ˈdres] for senses 1, 2, & 3 also [ˈa-ˌdres]

This might be confusing (noun senses 4 to 6 are dated, and sense 7 is for golf: the stance of the player and the position of the club).

The defunct Random House was better to some extent, still preferring the verbal pronunciation even for the noun but listing both for the noun and only the correct one for the verb. Even so, I’d have expected a more “traditional” approach from a dictionary having had the last edition in 2000, because it would have matched the reality of how people were actually speaking in the US!

The dual stress for permit as a noun is also mentioned by M-W, but only for the fish! Those lexicographers are nuts, all of them!

Notes on thesauri (not just Roget’s)

Thesauri or thesauruses, aka synonym dictionaries, are extremely valuable for writers, but most languages have pathetic thesauri. English has some good ones, but too many of them use “Roget’s” in their title—the same way so many used “Webster’s” for their dictionaries.

I assert that the best English language thesaurus ever was Rodale’s The Synonym Finder (1961, revised 1978), still unmatched today. Unfortunately, it never got reprinted, and even less updated with newer terms.

Speaking of “antiquities,” the Random House Roget’s College Thesaurus (last edition 2000) and Random House Webster’s College Thesaurus (last edition 2000, reprinted in 2005) weren’t that bad, but they could have been much, much better. They have the advantage of always giving a full sentence to exemplify the meaning for which a set of synonyms is given.

When I assess a thesaurus, I compare its entries for absolutism, limbo, meridian, naïve, naïveté (5 entries only!) with the corresponding entries in Rodale’s work (as PDF). And in most cases The Synonym Finder wins!

For compact editions in print, the 2-in-1 dictionary-cum-thesaurus ones that display the synonyms after the definitions can be very handy, once you accept their limitations. Decent editions (for their size) include Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary and Thesaurus (“Integrated Language Tools”) (1st Ed. 2007, updated in 2014), which has nearly 60,000 dictionary entries, of which more than 13,500 have thesaurus counterparts, and The American Heritage Desk Dictionary and Thesaurus (2005). M-W issued more recent editions as mass-market paperbacks, including Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary & Thesaurus (“Two essential references in one”) (2020) and Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary and Thesaurus (“Newly Revised & Updated!”) (2020) that claims “more than 60,000 dictionary entries” and “13,600 have thesaurus.” Too bad the paper is terrible. And two different editions issued the same year?!

For serious work, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus, 2nd Ed. (2019) isn’t a particularly bad choice, especially as it also gives “Related Words,” “Antonyms” and “Near Antonyms.” However, there are too many cross references; for instance, absolutism sends to DESPOTISM, despite wasting a lot of space defining the term and even giving an example!

It still doesn’t seem really updated: it includes gambler (see BETTOR) and gamester (see BETTOR), but not gamer. Duh.

But digital editions are more practical, right?

Well, on M-W.com, the thesaurus is more or less identical to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus, 2nd Ed. And there are links from a dictionary entry to the corresponding thesaurus entry. The website is what you should use, because the Android app, one more time, is a complete fuck-up!

Have you noticed how in the M-W app, sometimes the synonyms and antonyms are given at the end of the dictionary entry, and there’s no thesaurus entry for that word? At the same time, the web version behaves consistently. Check out the website:

- naive or naïve: dictionary, thesaurus

- naivety or naïvety: dictionary, thesaurus

- naivete, naïveté, or naiveté: dictionary, thesaurus

In the app, bugs galore:

- naive in the dictionary has synonyms and antonyms that are not in the online dictionary, then you’ll find examples that cannot be found online in either section!

- naive in the thesaurus has a structure that lacks some explanatory entities, such as instead of “1 as in innocent : lacking in worldly wisdom or informed judgment,” you’ll find “1 : lacking in worldly wisdom or informed judgment,” and this goes on for all the other meanings.

- naivety in the dictionary has many more synonyms and antonyms than in the online dictionary! Taken from the thesaurus entry, obviously.

- naivety in the thesaurus is pretty much OK.

- naivete in the dictionary is just like the online version, except that there is no thesaurus entry: there is no thesaurus tab to tap on, no matter how much you scroll up and down!

- If you search directly in the thesaurus for naivete, sometimes you get zero results, but if you search for naïveté, with proper French spelling, then you’ll find the missing entry! Some other times, the search will work, just like in the dictionary section, regardless of the spelling: naivete, naïveté, or naiveté. This seems to be an intermittent bug in the thesaurus. Either way, the connection between the thesaurus and the dictionary never works for this entry, so you won’t find a second tab to tap for this word! (Obviously, the previous caveat applies: instead of “1 as in innocence : the quality or state of being simple and sincere,” you’ll find “1 : the quality or state of being simple and sincere,” and so on.)

Note that the website has a specific presentation that cannot be found in the app: the “Synonyms & Similar Words” and the “Antonyms & Near Antonyms” are grouped in two, not four, categories, but each is colored by relevance in 3 shades of orange and blue, respectively. Cute.

But the mobile app seems to be for a different product and has too many bugs (and missing words, if you remember the case of zugzwang).

There are mobile apps for thesauruses from Oxford and Collins (from MobiSystems) and from Chambers (by Antony Lewis from WordWeb Software). While the Chambers Thesaurus is the most limited of the three, it has the advantage that all searches are full-text; therefore, even if there’s no entry for a word, it will be found listed as a synonym for another term.

While we’re at Collins, let me show you how they screwed up this brand lately. Consider two tiny works for kids, Collins English School Thesaurus 6th Edition (2018) and Collins Gem English School Thesaurus 6th Edition (2019). The choice of synonyms is baffling, such as random being listed as a synonym for absent-minded!

I asked them on Twitter in 2021 about that, to no avail. Find me a dictionary where random is listed as having this possible meaning, and I’ll eat it! (If it’s in Macquarie, I can’t possibly know.)

Do you know what I’m missing at times? I cannot access it right now, as mine in another country, but there’s a gizmo from the times (before 2005) when Franklin Electronics made devices such as this MWD-1470:

I don’t know what old version of Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary & Thesaurus such devices were using, but despite being limited as a dictionary, the thesaurus was something fabulous! Listed as the Franklin Thesaurus on the packaging, it has the unique feature of listing words from the same class. My favorite example: cambric did have an entry in the thesaurus, and it listed about two dozen types of fabric! Beat that: no printed thesaurus has an entry for cambric! (Cultural note: EN cambric, also batiste; FR depending on quality: chambray, linon, batiste; IT: cambrì, tela finissima analoga alla batista.)

Those were the times…

Intermezzo italo-francese

Since I mentioned some online Italian dictionaries, I’ll add here some information on more of them. The Italians are better lexicographers than the French, whose dictionaries are simply unprofessional, and let me open brackets within brackets to elaborate on this assertion.

Why French dictionaries suck big time

The Trésor de la langue française informatisé (TLFi), possibly the best monolingual French dictionary ever made, was frozen at its completion in 1994. It’s still useful, and it can be accessed on the site of CNRTL.

Le Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (DAF), after an 8th edition released in 1935, only released its 9th edition in 2024, despite having its first fascicle released in 1986 and its first volume in 1992. Volume 4 (R to Zzz) needed 13 years: 2011 to 2024! The result is pathetic; the definitions are shorter than expected, and citations are not given.

But did you know that the DAF was not directed by professional linguists? The work was overseen by the Académie française itself, whose members are writers, scholars, and public intellectuals, but not trained linguists. The entries were polished by lexicographers and editors, but that was on the technical side. The definitions were written by amateurs in the field!

The most famous linguistic name in Larousse. But it was almost never what people believed it to be, and it’s not developed in any meaningful sense, despite its yearly Le Petit Larousse and its smaller titles for school kids. Larousse was in trouble and changed hands multiple times since the 1980s: CEP Communication (1983), renamed to Compagnie Européenne de Publication (1984); Havas (1997); Vivendi Universal (1998) as Larousse-Bordas and then Larousse/VUEF; and Lagardère Group (2002), with a final integration in Hachette Livre (2004), itself a subsidiary of Lagardère.

BTW, Hachette had some nice dictionaries, especially the one-shot Dictionnaire universel francophone (DUF) Hachette (1995), but the retards never reedited it! (I’ll show you later why it’s a brilliant work, beyond the fact that it collected African and Québecois terms and meanings. It’s not available anymore, but I do have its definitions; the proper nouns weren’t supposed to be online, and I only got them because the server had a bug. Oh, the days of youth…)

Back to our sheep, Pierre Larousse started by creating the Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle aka Grand Larousse du XIXe siècle in 15 volumes (1866-1876) and two supplements (1878 and 1888). He used 89 contributors for a result of 24,000 pages. But he died in 1875, before its completion! It was truly encyclopedic. One could find in it even famous pharmacists or lawyers. After its eponym died, Claude Augé supervised the creation of the Nouveau Larousse illustré (1897-1904) in 7 volumes and a supplement, essentially a scaled-down, updated, and more neutral version.

The title that made the name of Larousse famous outside France, Le Petit Larousse Illustré, aka Le Petit Larousse, first appeared in 1905 and was based on Augé’s Dictionnaire complet illustré (1889). This one-volume work that has yearly updated editions and that, at some point, even had two distinct yearly editions, one black-and-white and one in color, each with different illustrations, has two main sections: a dictionary for common words and an encyclopedia of proper nouns. When Le Petit Larousse first appeared, Pierre Larousse had been dead for 30 years!

The sad part is that there were better works that died. First, the Grand Larousse encyclopédique en dix volumes, published by Larousse between February 1960 and August 1964, with two later supplements in 1968 and 1975. Luxury editions split into 22 and 24 volumes were issued in 1970 and 1976, respectively, but the contents were the same. An overhauled edition, split into 10 or 15 volumes but with identical contents, the Grand Dictionnaire encyclopédique Larousse (GDEL), was published 1982-1985. In 1986, it was renamed to Grand Larousse universel (GLU) in 15 volumes, and published in almost identical editions between 1987 and 1997. This effort has been lost forever, as nobody bothered to derive at least an electronic or an online edition. When this thing died, even Britannica wasn’t selling anymore: despite starting to develop a digital edition in 1994, Britannica was in deep red, and in 1996 was sold severely under its value. Even today, Britannica.com Inc.’s money comes from its Merriam-Webster titles, not from the online subscriptions to Britannica!

Today, the online edition of Larousse is undermediocre. But don’t expect much more from the printed editions, apart from proper names and illustrations.

Le Dico en ligne Le Robert is marginally better, but only marginally.

Dictionnaires Le Robert, founded by Paul Robert in 1951 as Société du nouveau Littré, was sort of a French Random House Reference, except that it’s still alive. If Random House Reference started with the American College Dictionary in 1947 to create the first Random House Dictionary of the English Language in 1966, it was still based on a 1927 dictionary. In contrast, Paul Robert started (with Alain Rey and Josette Rey-Debove, both lexicographers) the Dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française from scratch, with the first volume published in 1953 and the sixth in 1964, and a supplement in 1970.

This will later become Le Grand Robert, the largest French language dictionary to date (no encyclopedic entries): 6 volumes and 13,420 pages (1984-2001). Le CD-ROM du Grand Robert, version 2.0, was issued in 1995. No later standalone edition ever existed, as now you’re supposed to pay an expensive subscription to an online dictionary that is, I’m pretty certain, almost never updated. With so few subscriptions and a negligible market share, why bother, and with what money?

The famous Le Petit Robert first appeared in 1967, with future editions in 1977 and 1993. Only since 2000 has it yearly editions. Its definitions are more professional than Larousse’s but still subpar. The online subscription is also too expensive for what it is! Also, they started to add citations from random nobodies (wokism!—see iel), much like M-W. At least Le Grand Robert has quotations from major authors!

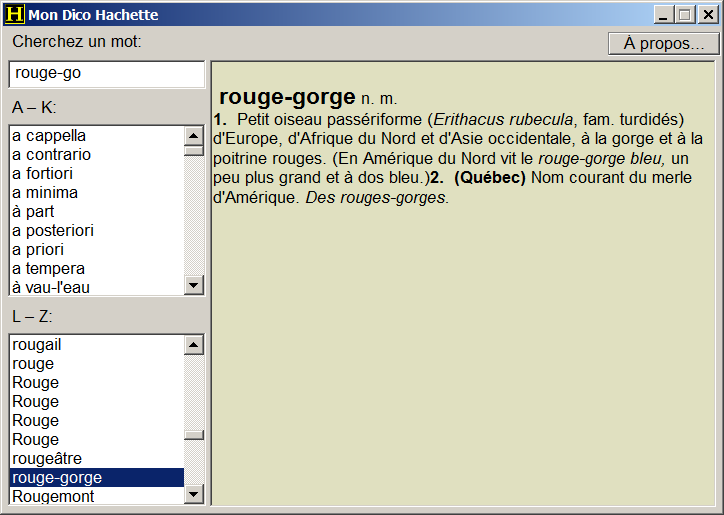

But here’s a shocking fact: the French and the Spanish are the only major cultures whose dictionaries don’t mention the scientific names of plants and animals!

Two Romance-language nations that are so nombrilistic that they couldn’t care less about Latin, except in very specialized dictionaries! This bird? Oh, “a small bird with a red chest and this and that.” This other thing? Well, “a small blue fish, etc.” But no clear, unequivocal identification through the internationally recognized pivot, the Latin name!

Can the French dictionaries mention that the European robin has the scientific name of Erithacus rubecula? No, they cannot.

rouge-gorge, rouges-gorges

nom masculin

Petit passereau brun (muscicapidé) des bois, parcs et jardins, à face, gorge et poitrine d’un rouge vif, sédentaire, présent presque partout en France.

rouge-gorge

nom masculin

Oiseau passereau à gorge et poitrine d’un roux vif. Des rouges-gorges.

ROUGE-GORGE nom masculin (pluriel Rouges-gorges).

Étymologie : XVe siècle. Composé de rouge et de gorge.Petit oiseau de l’ordre des Passériformes, répandu dans toute l’Europe, dont le devant de la tête, la gorge et la poitrine sont d’un rouge orangé.

TLFi:

ROUGE-GORGE, subst. masc.

ORNITH. Oiseau de l’ordre des Passereaux, du genre Fauvette, de la famille des Turdidés assez proche du rossignol et caractérisé par la couleur rouge sombre de la gorge et de la poitrine. Un bruissement féroce d’ailes hétérogènes et cinglantes depuis le crépitement léger des petits rouges-gorges, aux tui-tui colorés (…), jusqu’au ronflement sourd, prolongé en rumeur des grands corbeaux voraces (Pergaud, De Goupil, 1910, p. 191).

Le Grand Robert (édition 2005):

rouge-gorge n. m.

ÉTYM. 1464; de rouge, et gorge.♦ Oiseau (Passereaux, Turdidés) assez proche du rossignol, de petite taille, dont la gorge et la poitrine sont d’un roux vif (→ Matinal, cit. 3; pâture, cit. 2). | Le rouge-gorge est insectivore. (On l’appelle aussi rubiette). | Des rouges-gorges.

They must be kidding. Passereaux is the entire order Passeriformes, which includes more than half of all bird species! Turdidés, or the passerine bird family Turdidae, includes 17 genera and more than 167 species! The only correct classification is Erithacus rubecula!

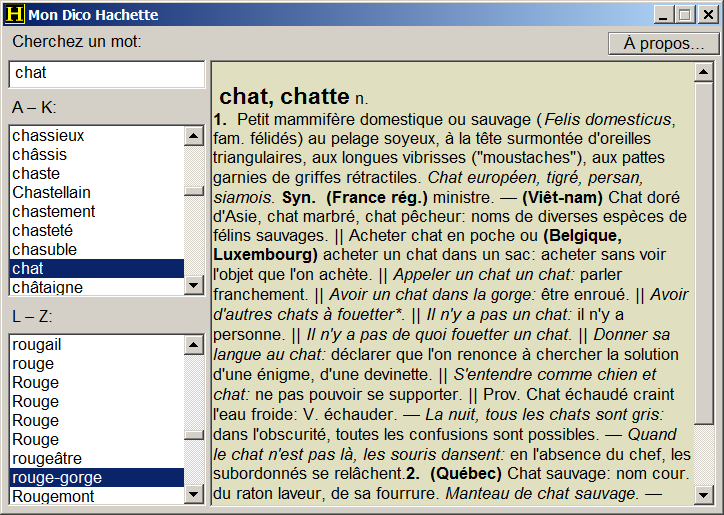

How about the cat? Can they mention Felis catus? Obviously, they can’t!

chat

nom masculin

(bas latin cattus)

1. Mammifère carnivore (félidé), sauvage ou domestique, au museau court et arrondi.

chat, chatte

nom et adjectif féminin

I. 1. Petit mammifère familier à poil doux, aux yeux oblongs et brillants, à oreilles triangulaires, aux griffes rétractiles. ➙ matou ; familier minet. Chat de gouttière. Chat angora, siamois. Le chat miaule, ronronne. Une chatte et ses chatons.

This is even wrong: chat is masculine!

CHAT, CHATTE nom

Étymologie : XIe siècle. Du bas latin cattus, « chat (sauvage, puis domestique) ».1. Petit mammifère carnivore de la famille des Félidés. Le chat a le pelage soyeux, le museau court, les oreilles triangulaires. Un chat qui fait ses griffes. Chat domestique. Chat errant. Un chat sauvage. Un chat noir, tigré. Un chat persan bleu. Une chatte angora, siamoise. Chat de gouttières ou de gouttière, ou chat européen, chat d’une espèce commune en Europe. Le miaulement du chat. Le chat ronronnait, faisait le gros dos. Rôder comme un chat. Le chat guette la souris. Une peau de chat, la dépouille de cet animal, utilisée comme fourrure et, autrefois, dans certaines expériences de physique. (Par analogie. Iron.) Chat fourré, magistrat revêtu de son hermine.

TLFi:

CHAT1, CHATTE, subst.

I.−

A. ZOOL. Genre de mammifères carnivores de la famille des Félidés comprenant le lion, le tigre, la panthère, le lynx, etc. Nom sc. felis. Chat haret, chat sauvage, chat-cervier (v. aussi chat-pard, chat-tigre) : | Le Small Cat House ou Home des félins mineurs, m’attire par ses exquis ocellots sud-américains, petites panthères miaulantes, son « léopard nébuleux » d’Assam, acheté en 1925, ses étranges bêtes presque inconnues, ce ratel à dos blanc, ce panda de l’Himalaya à queue d’écureuil et visage de loulou de Poméranie, qui pivote sur lui-même éternellement, comme le globe terrestre, ce gros chat gris de la Pampa, ce chat d’or, ce chat–pêcheur, et enfin ce lynx ravissant de Gambie, à oreilles noires, où les touffes de poils font des nœuds de rubans. MORAND, Londres, 1933, p. 132.

− En partic. région. (Canada). Chat (sauvage). Raton laveur. Capot de (ou en) chat sauvage. | Capot de chat bien fourré (Cl. JASMIN, L’Outaragasipi, Montréal, 1971, p. 51).

B.− Lang. cour. Chat de gouttière, chat domestique. Petit animal domestique carnassier, à pelage de couleur variée souvent noir ou gris, se nourrissant de souris, de petites proies, et de la nourriture servie par ses maîtres. Chat noir, gris, tigré; petit chat, mère-chatte; chat angora, chartreux, persan, siamois; miaulement, ronronnement de chat. | Un joli chat noir avec de grands yeux verts (CHAMPFLEURI, Les Aventures de Mlle Mariette, 1853, p. 72): etc.

Oh, at least we have this tiny mention: “Nom sc. felis.” But TLFi is sometimes absurd with its ubuesque complexity: first the species (A), and then a specimen (B)! WTF.

Le Grand Robert (édition 2005):

chat, chatte n.

ÉTYM. V. 1170; du bas lat. cattus.I 1 Petit mammifère familier à poil doux, aux yeux oblongs et brillants, à oreilles triangulaires, se nourrissant de petits animaux (traditionnellement, de souris qu’il aime à chasser) et de la nourriture que ses maîtres lui servent; spécialt, le mâle (→ Matou) adulte. | Chat domestique. → (fam.) Miaou (enfantin), minet, minou, mistigri. | Relatif au chat. → 2. Cataire. | Chat coupé, châtré. | Chat blanc, bleu, crème, gris, noir, roux; écaille, pie; marbré, tigré. | Chat à poil court, à poil long. | Chat commun, chat de gouttière. | Chat de race : abyssin, chartreux, siamois; birman, persan (dit anciennt chat angora). | Les Chats, poème de Baudelaire (Fleurs du Mal, 35 et 52). | Le chat botté, héros d’un conte de Perrault. | Les griffes, les moustaches, les yeux fendus du chat. | Il ne faut jamais couper les moustaches (cit. 9) à un chat. | La queue du chat. | Le chat miaule (→ Miaou, miaulement). | Le chat ronronne, fait le gros dos. | Le chat fait ses griffes. Le chat rentre ses griffes, fait patte de velours. | La souplesse, l’élégance du chat. | Chat souricier, tueur de souris, de rats. | Avoir un chat. | Le chat de la voisine. | « C’est la mère Michel Qui a perdu son chat » (chanson). | Donner du lait, du poisson, du mou à son chat. — Une portée de petits chats (chattée). — Boyau de chat. → Catgut. | Peau de chat. | Pelage, fourrure du chat. — Chat retourné à l’état sauvage. → Haret.

etc.

This is not how a dictionary should be made!

Now, guess (you can’t!) which dictionary is made in the “international style”? Sure enough, le Dictionnaire universel francophone Hachette, the one they abadoned after its unique 1995 edition!

rouge-gorge n. m.

1. Petit oiseau passériforme (Erithacus rubecula, fam. turdidés) d’Europe, d’Afrique du Nord et d’Asie occidentale, à la gorge et à la poitrine rouges. (En Amérique du Nord vit le rouge-gorge bleu, un peu plus grand et à dos bleu.) 2. (Québec) Nom courant du merle d’Amérique. Des rouges-gorges.chat, chatte n.

1. Petit mammifère domestique ou sauvage (Felis domesticus, fam. félidés) au pelage soyeux, à la tête surmontée d’oreilles triangulaires, aux longues vibrisses (“moustaches”), aux pattes garnies de griffes rétractiles. Chat européen, tigré, persan, siamois.

etc.

That was a primitive software I made in 2001, with imperfect processing of the text. Maybe I should give it a second try.

But the main idea is that the French made a proper dictionary only once, then they killed it.

Now, any decent Italian dictionary knows the drill.

lo Zingarelli 2026:

pettirosso [detto così dal colore rosso del petto ☼ 1481] s. m.

❖ (zool.) uccello piccolo e vivace dei Passeriformi, buon cantore, con piumaggio caratterizzato da una macchia rossa su petto e gola (Erithacus rubecula)gatto [lat. tardo căttu(m), di etim. incerta ☼ 1211]

A s. m.

1 ❖ (f. -a) (zool.) felino domestico, con corpo flessuoso, capo tondeggiante, occhi grandi e unghie retrattili, con un gran numero di razze (Felis catus)

● gatto delle selve, servalo

● gatto marmorato, felino di aspetto simile al gatto che vive nell’Asia meridionale e insulare e ha pelame bruno-grigio macchiettato e abitudini strettamente notturne (Pardofelis marmorata)

● gatto marsupiale, dasiuro

● gatto selvatico, felino di piccole dimensioni, molto simile al gatto domestico, di cui è il probabile progenitore; è diffuso in tutto il mondo con numerose sottospecie (Felis silvestris)

● gatto di Pallas, manul

● essere come cane e gatto, essere sempre pronti a litigare

● essere in quattro gatti, in pochissimi

● (fig.) gatto a nove code, staffile con nove strisce di cuoio, usato un tempo per punizioni corporali

Prov. quando non c’è il gatto i topi ballano, in assenza di controlli tutti ne approfittano per fare i propri comodi

il Devoto-Oli 2017:

pettirosso s.m.

~ Uccello dei Turdidi (Erithacus rubecula), bruno-olivastro nelle parti superiori, rosso-arancione sulla faccia, la gola e il petto, biancastro sul ventre.

ETIMO Comp. di petto e rosso

DATA sec. XVI.gatto s.m. (f. -a)

1 Mammifero dei Felidi (Felis cattus), domesticato da lungo tempo per compagnia e per la cattura dei topi; ha corpo agile e flessuoso, capo più o meno rotondo secondo le razze, vibrisse, o baffi, sul labbro superiore, zampe corte con unghie retrattili: gatto soriano, siamese, persiano │ Gatto selvatico (Felis silvestris), felide delle foreste dell’Europa centr., merid. e orient., lungo più di 1 m, con pelliccia folta di color grigio-fulvo o grigio-nerastro e coda con anelli neri │ Gatto viverrino (Felis viverrina), vivente nelle foreste e nelle zone paludose dell’India, dello Sri Lanka e di Taiwan, gran cacciatore di pesci, che fa saltare fuori dall’acqua a colpi di zampa ║ (fig.) Con riferimento alle sue qualità e caratteristiche: essere agile, furbo come un gatto; vederci al buio come i gatti. │ Essere come cane e gatto, vedi cane │ (In) quattro gatti, (in) pochissimi │ Gatto lupesco, personaggio fiabesco nel quale si incontra l’astuzia del gatto con la ferocia del lupo ║ (gerg.) Ladro │ Poliziotto.

etc.

ETIMO Lat. tardo cat(t)um (sec. IV), di origine oscura

DATA sec. XIII.

The French are simply retarded.

But the Belgians aren’t any better: they killed Le Grevisse!

Nous vous remercions pour l’intérêt que vous portez à notre ressource Le Bon usage électronique.

Confrontés à des problèmes indépendants de notre volonté, nous avons dû nous résoudre à arrêter la commercialisation de notre ressource Le Bon usage électronique à compter du 31/12/2022.

Depuis le 01/01/2023, nous ne pouvons plus vendre d’abonnements individuels ou institutionnels, ni permettre l’accès aux 3 mois mentionnés dans la 16e édition.

Le livre papier Le Bon usage (16e édition) est toujours disponible sur notre site ou chez votre libraire.

Large common monolingual Italian dictionaries

- Grande Dizionario Italiano di Aldo Gabrielli, Quarta edizione (Hoepli, last edition 2020)

- Grande Dizionario di Italiano (Garzanti, last edition 2020)

- Dizionario Italiano Sabatini Coletti (Hoepli, nuova edizione 2024 has minor additions to the 2020 edition)

- Il nuovo Devoto-Oli (Mondadori, yearly editions) – with all its faults, I preferred the “old” Devoto-Oli, which had its last edition for 2017 (released in 2016)

- lo Zingarelli (Zanichelli, yearly editions) – 2026 edition released in August 2025

Bilingual with English

- Oxford Paravia (outdated and out of print)

- Sansoni Inglese (outdated and out of print; digital eLexico 2012 edition still available)

- Grande Dizionario Hazon di Inglese (Garzanti, last edition 2014)

- Grande dizionario inglese di Fernando Picchi, sesta edizione (Hoepli, last edition 2023, or 2023 digitally, with minor additions to the 2020 edition)

- il Ragazzini, Quarta edizione aggiornata (Zanichelli, 2024)

Bilingual with French

- Grande Dizionario Francese (Garzanti, 2014, probably based on the Garzanti-Petrini that had the last edition in 2004)

- Sansoni Francese (outdated and out of print; digital eLexico 2019 edition still available)

- il Boch, Settima edizione (Zanichelli, 2020) – also printed in France by Le Robert

Maverick: Vallardi

- Dizionario maxi/flexi Italiano Vallardi, identified by “1530 pagine” (1536 for the 2021 Flexi and 2022 Maxi edition, then returning to 1530) and “Oltre 280.000 voci e accezioni” and reprinted in soft and hard cover every 1-2 years. The 2025 editions are the 2023 editions with a sticker having a different ISBN. And I’m pretty sure they’re all reprints of the 2018-2019 editions. However, this dictionary is quite comprehensive and very practical, with clear definitions and useful examples, a section with acronyms that’s better than the one in Zingarelli, and the price is bafflingly low (the paper is cheap, though): €19.90 (€18.90 previously) for Maxi (hardcover) and €15.90 for Flexi.

- Dizionario maxi/flexi Inglese Vallardi – similar behavior; “1560 pagine” and “Oltre 300.000 voci e accezioni”

- Dizionario maxi/flexi Francese Vallardi – similar behavior; “1216 pagine” and “Oltre 250.000 voci e accezioni”

Digital editions

- Hoepli’s dictionaries have Android/iOS editions by Edigeo and Windows/macOS/Linux (Electron-based, previously Java-based) editions by eLexico.

- Il nuovo Devoto-Oli has Android/iOS apps that can be installed on 2 devices at most. Yearly subscription. Even if you don’t have any active subscription, you just cannot use your account on an app installed “on a 3rd device,” even if the previous 2 devices physically don’t exist anymore. It happened to me, and I wrote to them, but I got no reply other than «La sua richiesta (“Hai già attivato l’app su due dispositivi, non puoi attivarla su altri.”) è stata ricevuta e registrata dal sistema con l’ID 551740 e verrà esaminata dagli operatori del servizio clienti il prima possibile.» Assholes is too kind a word; they’re retarded shitheads.

- Zanichelli’s dictionaries have Android/iOS/Windows/macOS editions and can also be accessed in a browser. Lo Zingarelli is subscription-only (€13.10/yr), and so is il Ragazzini, despite not being released in print yearly (every two years). Il Boch can be used with a yearly subscription or with a perpetual €33.90 license. Perpetual licenses mean Android/iOS/Windows/macOS can run indefinitely, but online access in a browser only works for 5 years. Until 2022 (2023 editions), separate Android/iOS existed for Ragazzini/Boch. Only people who purchased them back in the day can still access and install them (il Ragazzini 2019; il Ragazzini 2021; il Ragazzini 2023; il Boch 6e; il Boch 7e). I purchased il Boch for €19.99 in July 2022, but it only works in that app, not online and not in the Dizionari Zanichelli app.

Free online editions

- Grande Dizionario Hoepli Italiano di Aldo Gabrielli 2018 su la Repubblica: https://dizionari.repubblica.it/italiano.html

- Grande Dizionario Hoepli Inglese di Fernando Picchi 2018 su la Repubblica: https://dizionari.repubblica.it/inglese.html

- Grande Dizionario Hoepli Italiano di Aldo Gabrielli su Hoepli.it: https://grandidizionari.hoepli.it/Dizionario_Italiano/

- Dizionario di francese di Florence Bouvier, Edizione Compatta: https://grandidizionari.hoepli.it/Dizionario_Italiano-Francese/

- Dizionario della lingua italiana Sabatini Coletti 2018 sul Corriere: https://dizionari.corriere.it/dizionario_italiano/

- Dizionario dei Sinonimi e dei Contrari di Michele Giocondi: https://dizionari.corriere.it/dizionario_sinonimi_contrari/

- Il Nuovo De Mauro 2018: https://dizionario.internazionale.it/

- Il Vocabolario Treccani: https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/

- Dizionari Medi Garzanti di Italiano, Inglese, Francese, Spagnolo, Tedesco, versioni free: http://www.garzantilinguistica.it/

- Vari dizionari su Sapere.it: https://www.sapere.it/sapere/dizionari.html

- Dizionario Italiano on line a cura di Enrico Olivetti (Olivetti Media Communication, Philippines): https://www.dizionario-italiano.it/

- Dizionario della lingua italiana Tommaseo-Bellini (1861) Zanichelli – Accademia della Crusca: https://www.tommaseobellini.it/

- Grande dizionario della lingua italiana GDLI (1961-2002, 2004, 2009) UTET – Accademia della Crusca: https://www.gdli.it/

The last one, GDLI, was really the greatest Italian dictionary ever! Fabulous work.

The previous one, from 1861: Niccolò Tommaseo was the Italian equivalent of Émile Littré.

BONUS: Accademia della Crusca — Consulenza linguistica is the equivalent of Académie française — Questions de langue + Dire, ne pas dire (Emplois fautifs; Extensions de sens abusives; Anglicismes, Néologismes & Mots voyageurs; Expressions, Bonheurs & surprises; Bloc-notes; Courrier des internautes).

In the cases of both Academies, the respective sites are a complete PITA: they look like shit, their usability is ZERO, and without using the search function, navigation is futile. I guess they charged with the task someone who last built a site 25 years ago. The Italian site has strange fonts, and the French one is a huge mess.

The Italians seem more tolerant of Anglicisms: customizzare, customizzazione (lo Zingarelli); photoshoppato (Devoto-Oli).

Discussion

Since I said that I liked the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (and Random House Webster’s College Dictionary on paper, for practical reasons), let me add that the equivalent for Italian would be the Grande Dizionario Italiano di Aldo Gabrielli aka il Gabrielli: most definitions are using a language that I happen to like.

Unfortunately, this is an outdated dictionary, and it shows it. The relatively recent revisions were merely cosmetic, without adding recent terms.

At some point, I thought the Dizionario Italiano Sabatini Coletti (il Sabatini Coletti) to have more comprehensive definitions, but I found it annoying at times.

Then I became a fan of il Devoto-Oli: with yearly updated editions since 2004, il Devoto-Oli 2017 (released in 2016) had some charming definitions. That was the last digital edition before the reworked il Nuovo Devoto-Oli, released in 2017 as il Nuovo Devoto-Oli 2018 (leaflet), then also updated yearly. While the effort is commendable, this came with some unwanted changes: (1) Only the digital edition includes 120,000 entries; the printed one only has 75,000; (2) The “Nuovo” line has been overcomplicated with additions such as “Parole minate,” “Per dirlo in italiano,” “Questioni di stile,” which are not usage notes at the respective entries, but separate creations that could have been separate books! Instead of polluting the printed edition with such crap, they could have included all the entries available in the online edition! (3) There is no preview or trial whatsoever (there used to be in the past) of the online edition, so one cannot even know what it looks like! (4) The app can only be installed on 2 devices at most, and it’s impossible to remove a device that’s no longer active. If you don’t have an active license, you can’t log online to a dashboard where, hopefully, you could be able to remove devices. Whoever managed the software project was a complete retard.

Generally, lo Zingarelli is the most reliable of the only two monolingual Italian dictionaries that are updated yearly (even more often in digital form).

■ Random facts and comparisons:

- The 2024 “new” edition of il Sabatini Coletti is mostly a cosmetic review, with very few added words, mostly related to technology, such as chatbot. But it doesn’t include words that are recent but common, e.g. for objects one can find in a supermarket: spruzzino (=spruzzatore, nebulizzatore). Strangely enough, this meaning is recent, but since 1892 this word was used for a worker specialized in spray painting furniture with an airbrush. Nope. Missing.

- Actually, only lo Zingarelli includes spruzzino. And umarell. (I don’t have access to il Devoto-Oli editions newer than 2021.)

- A term known since 1967 (for a good reason), cicciobomba, can only be found in lo Zingarelli and il Devoto-Oli. Go figure.

- If it weren’t for the digital editions, both il Sabatini Coletti and lo Zingarelli would be impractical at times. Say, veramente is at the end of the entry for vero, whereas it’s a separate entry in il Gabrielli and il Devoto-Oli. Heck, even in il Nuovo Devoto-Oli Junior released in 2015, veramente has its own entry! (They killed the digital edition by eLexico; the newer edition released in 2022 in print has a code to activate an the online access in a browser. With only 26,000 entries, il Nuovo Devoto-Oli has exceptionally clear definitions, meant for kids but also useful to those learning Italian as a foreign language.)

- The perfect example that illustrates how dated il Gabrielli is: smanettare (=to tinker, to fiddle; FR bidouiller) and smanettone (=tinkerer, geek, computer freak, tech whiz). The concept behind these terms has undergone a semantic shift over decades.

Only il Gabrielli preserves the original skepticism towards someone who fiddled with technology without really knowing what they were doing: “Trafficare con discutibile competenza attorno ad apparati tecnologici quali apparecchi radioriceventi e trasmittenti, computer e altro.”

The contemporary view is that of someone who’s comfortable with tech and competent enough, even if not formally trained. Everyone else is using it:

il Sabatini Coletti: “Utilizzare con dimestichezza e scioltezza un apparecchio e simile.”

il Devoto-Oli: “Usare un computer con disinvoltura e abilità.”

lo Zingarelli: “Utilizzare con disinvoltura e abilità computer, programmi, congegni, ecc.”

One more supermarket product: fiocchetto, something that looks like prosciutto crudo, but it’s different.

Guess which dictionaries never heard of it, and their only food-related meaning is about pasta?

il Gabrielli 2020

2 (al pl.) Pasta alimentare da fare in brodo, a forma di piccoli fiocchiil Sabatini-Coletti 2020 and 2024

2 (al pl.) Pastina da cucinare in brodo a forma di piccolo fiocco

On the other hand…

lo Zingarelli 2026

4 ❖ salume fatto con la parte interna e magra della coscia del maiale, salata e stagionata; specialità parmenseil Devoto-Oli 2017

3 Salume costituito dalla parte interna, quasi completamente magra, della coscia del maiale, salata e stagionata con un procedimento molto diverso da quello usato per il prosciutto; specialità emiliana.il Devoto-Oli 2021

5 (gastron.) Salume costituito dalla parte interna e magra della coscia del maiale, salata e stagionata; specialità emiliana.

En passant, let’s notice how the “Nuovo” Devoto-Oli has been abridged by removing useful information from the definitions. The last “classic” edition, 2017, had much better definitions.

■ Going fishing (or not):

In the section about Merriam-Webster, I mentioned trabacolo (the wrong, AmEn spelling of trabaccolo) and bragozzo.

- Il Gabrielli mentions at trabaccolo: “SIN bragozzo.”

- Il Sabato Coletti, at trabaccolo: “è detto anche bragozzo.”

- Il Devoto-Oli: “trabaccolo s.m. ~ Bragozzo.”

- But lo Zingarelli prefers to give distinct definitions to both words, with no cross-references:

- trabaccolo s. m. ❖ (mar.) nave a vela da trasporto e pesca, tipica del mar Adriatico, con prua e poppa rigonfie, attrezzato con due alberi e vele al terzo, bompresso e polaccone

- bragozzo o bracozzo s. m. ❖ (mar.) tradizionale barca da pesca in legno caratteristica dell’alto Adriatico, fornita di ponte con prua e poppa tondeggianti, due alberi e vele al terzo, scafo e vele decorati a colori vivaci

- The same is true for Treccani (trabaccolo, bragozzo):

- trabaccolo s. m. [affine a trabacca]. – Piccolo veliero da carico che esercitava il cabotaggio lungo tutto l’Adriatico e lo Ionio, interamente pontato, con due alberi muniti di vele al terzo caratterizzate dal fatto di essere sospese l’una a dritta e l’altra a sinistra del proprio albero, in modo da permettere una ottimale andatura a pieno carico con il vento spirante da poppa (la cosiddetta «andatura o velatura a trabaccolo» per navigare a farfalla); tipi più grandi, nella seconda guerra mondiale, furono impiegati come batterie galleggianti costiere.

- bragozzo s. m. [voce veneta, di etimo incerto]. – Piccolo veliero a scafo di legno, di forme rotonde e tozze, in genere a due alberi con vele dipinte a vivaci colori, largamente usato nell’Alto Adriatico, per pesca o trasporto.

Was a bragozzo only used for fishing, whereas a trabaccolo was multipurpose (lo Zingarelli), or maybe cargo-only (Treccani: “da carico”)? And did a bragozzo have particularly colorful sails? Wikipedia’s images don’t help at all (trabaccolo, bragozzo), and according to Wikipedia, both vessels were “da pesca e/o da carico.”

One cannot trust the lexicographers from lo Zingarelli and Treccani.

■ How software developers suck (part one):

Based on the difference between the databases of the Android app versions 1.0 and 2.0, il Gabrielli got 236 new entries between 2018 and 2020: 94,556 vs. 94,792 entries. But a later update lost 4 entries! Here’s how.

The original 2020 digital edition has wrong division into syllables for 176 words (entries). I don’t know if the printed dictionary has correct syllabification for all words, but the eLexico software (database version 20.1), which did not issue an update, still has these errors. All the others have the respective words correctly separated into syllables: il Sabatini Coletti, il Devoto-Oli (even 2017!), lo Zingarelli.

But the app issued an update towards the end of July 2022. Alongside the fixing of the syllabification for 176 entries, this update:

- Incorrectly changed the entry biossido to bi-ossido.

- Simply lost these 4 entries: biocucina, cinecittà, polaroid, polaroide.

How was this even possible?!

As a side note, il Gabrielli only considers cinecittà to be a common noun; therefore even the MGM Studios were “a cinecittà.” Compare to:

- il Devoto-Oli also uses a small initial C, and the definition suggests a generic name: “Centro attrezzato per la produzione cinematografica su scala industriale.” Only the etymology mentions the true one: “dal nome della “città del cinema” voluta a Roma dal regime fascista e inaugurata nel 1937.”

- lo Zingarelli only knows of the Cinecittà, with capital C, the one and only “grande complesso per la produzione cinematografica su scala industriale, situato alla periferia di Roma.”

- il Sabatini Coletti lists it with a small C, but after the “Nome degli stabilimenti cinematografici costruiti al Quadraro, presso Roma, nel 1937,” it accepts, by extension, any “complesso per la produzione industriale di film.” Still, at least the original studios should have had a capital C!

■ Short notes on bilingual ones:

1. For bilingual dictionaries with French, il Boch is the largest one available digitally, and it’s also the only one updated not very long ago.

That’s because you should ignore il Sansoni Francese for Windows/macOS/Linux; a database from 2019 isn’t that old, but Sansoni is bloated with countless “frasi e costruzioni” that shouldn’t be there. Imagine an English dictionary that, at the entry “red,” would include as examples with translations “red carpet,” “red cow,” and “red flower,” none of which is idiomatic! (OK, “red carpet” is idiomatic, and it should be included at “carpet” or listed as a separate entry.)

Back to il Boch, don’t expect to find many differences between la 6° edizione 2014 and la 7° edizione 2020. There are some new terms, such as bidonvillisation, benchmark, complotiste, microbiome, mono-horaire, post-vérité, vapoter (they don’t give any examples as to which new entries have been added in the Italian section!), but there are so many missing entries or meanings in both sections! And I mean old words and old meanings!

But what pisses me off the most is a lack of sync between the sections that can be found in most bilingual dictionaries. Something like this:

- FR word_fr_1 → IT word_it_1

- IT word_it_1 → FR word_fr_2

Or:

- FR word_fr_1 → IT word_it_1

- IT word_it_1 doesn’t exist as an entry!

Or, if there are several translations per term:

- FR word_fr_1 → IT word_it_1, word_it_2

- IT word_it_1 → FR word_fr_2 or maybe IT word_it_2 → FR word_fr_3

For fuck’s sake! Complex entries with many meanings, examples, and expressions are difficult to synchronize, but it’s so frustrating when entries that only include 1 to 3 possible translations are completely disconnected between the translation directions!

2. For bilingual dictionaries with English, il Picchi (Hoepli 2020) is really large (182,219 entries when both directions are counted), and it has mobile and desktop apps with a one-time payment. Zanichelli’s il Ragazzini (2025, issued 2024) is only available as a subscription, and it’s most likely not larger if we only count the entries, not the “voci e significati.” The blurb mentions climate denial, large language model and ultra-processed among the new words, but there are older words that will probably never enter this dictionary. (This happens to all dictionaries.) Note that the digital version has 30,000 specialized terms that cannot be found in print.

My discontent regarding the lack of some recent terms is justified, because it’s a subscription thing! But let me give you an example of how they included relatively newer terms with subpar translations. Remember that meaning of the verb “to roast” that I wrote about? Well, il Picchi doesn’t know about it, but il Ragazzini does:

5 (fam. USA) prendere in giro; sfottere (pop.)

Well, no. They should have done like they sometimes do with untranslatable terms, meaning to explain instead of offering a broken translation. Roasting is a cultural ritual specific to the United States: a roast isn’t just mocking, teasing, razzing, or whatnot. It’s a staged event, often with a panel of comedians or friends, where the honoree is humorously insulted in front of an audience. The paradox is that the sharper the jokes, the more they signal respect and affection. This ritual doesn’t have a direct equivalent in other languages and cultures, and this is why in many languages the English roast is kept intact, especially in media contexts, because it’s seen as a genre name.

Obviously, you should ignore il Sansoni Inglese for Windows/macOS/Linux; its database is from 2012, and it’s also bloated with crap.

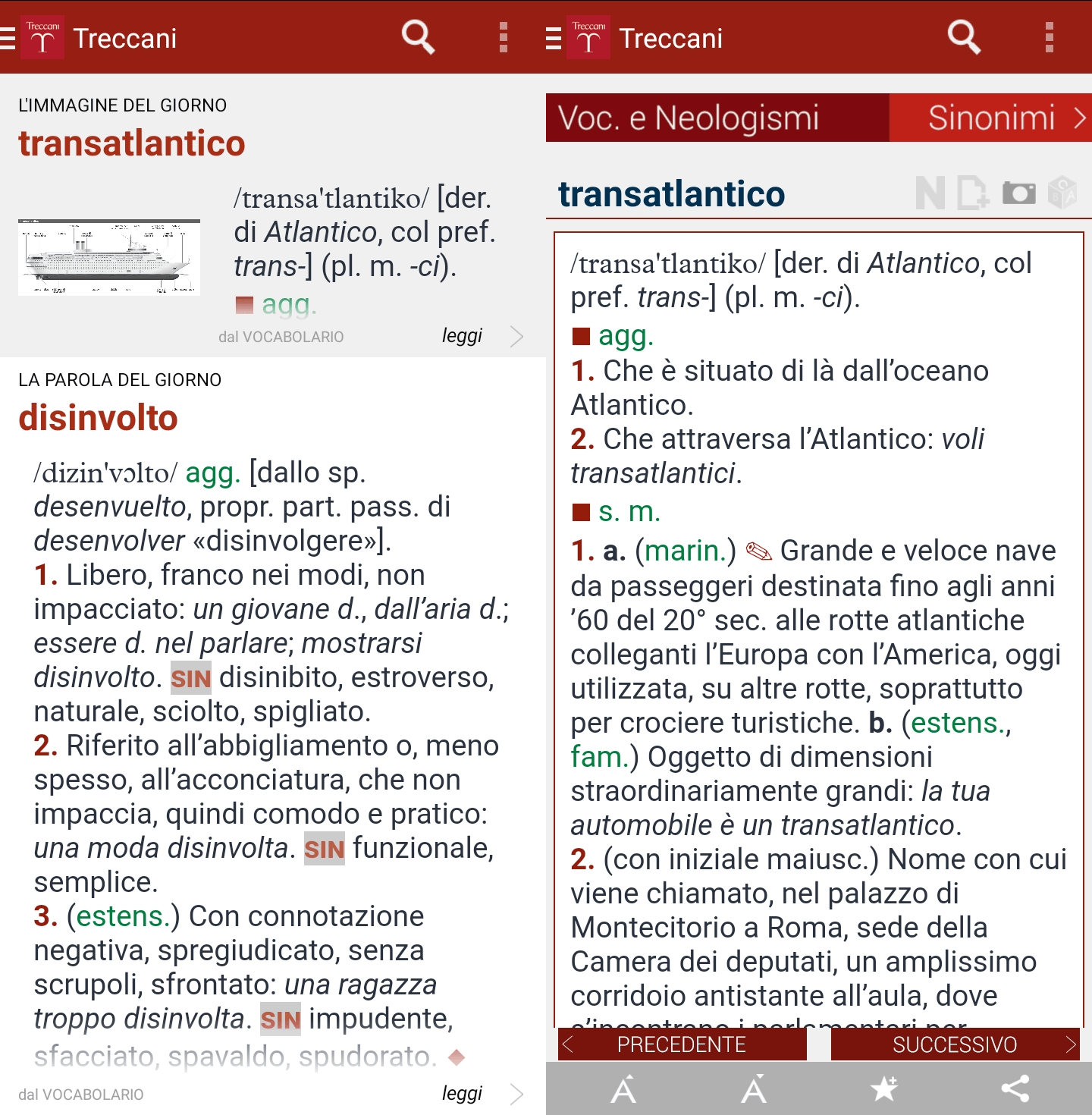

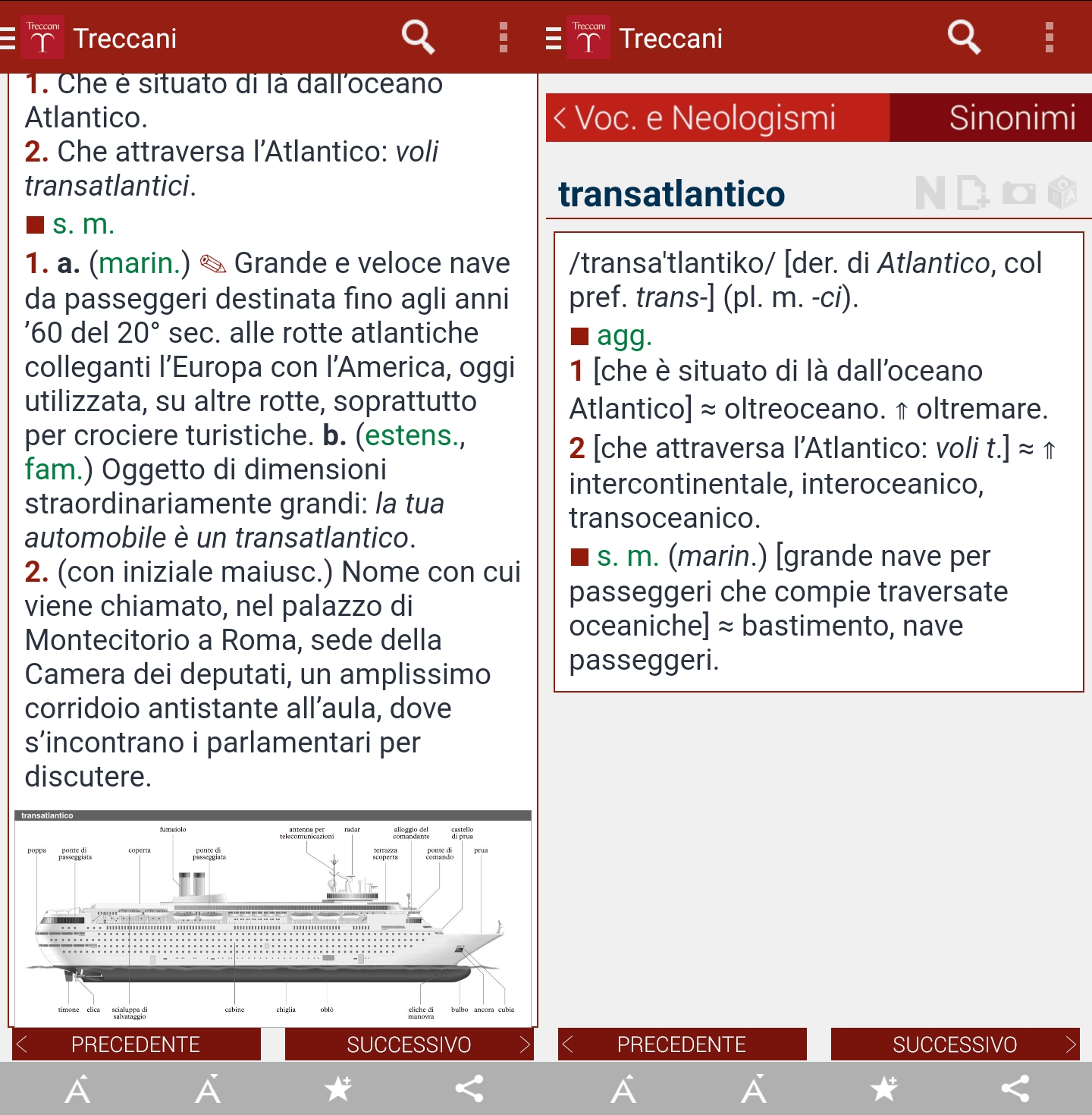

The Treccani case

In 2014, I fell in love with Treccani. Not the website, but the Android app. I even hacked it to correct its formatting to a form more pleasant to the eye. I corrected some formatting (I also broke some, but I procrastinated the fixing until I abandoned it). That edition has a fabulous mix of dictionaries:

- Il Vocabolario Treccani, with excellent definitions, an impressive number of expressions, proverbs, citations, and examples, and 255 images.

- A dictionary of synonyms, with 80 images showing regional terms.

- A dictionary of neologisms, most of them from the press, so related to politics rather than technology. This one was mixed with the Vocabolario, and when an entry belonged to it, a light gray “N” became darker.

With my adjusted styling, this is how it started (with a random image of the day), how a definition looked (the images were zoomable), and how a synonym entry was displayed. I could have chosen a better example, but any common word would have required a lot of scrolling.

Guess what they did the following year? They “simplified” the app, which now only contained the “normal” dictionary, without neologisms and synonyms! Also, the start screen looked like shit.

For the 2018 version of the app, to match a new edition in print, they changed some of the 255 images. They even removed some images (calcolatore, walkman) to add new ones (smartphone, smartwatch) without changing the total of 255!

■ How software developers suck (part two):

The problem? The images were embedded in the APK, but the developers (apparently, Andrea Gava and Camilla Macro) forgot to add the code that would display them! They also borked the database, because some words that were present in the 2014 and 2015 versions, and also in the online edition, were missing: speakeraggio, zama, and who knows how many others? (I didn’t compare the databases.) If you thought they couldn’t screw it up further, here’s another one: they have included two identical databases in the app, dizionario_pay_lemma_norm_fix_2.sqlite and dizionario_pay_lemma_norm_fix_5.sqlite! (By “fix” they meant “broke”…) And people were supposed to pay for such crap!

Tell me again about Italian software! Or German software. Or French software. Or software that hasn’t been tested by me.

OK, here’s for 2015 and 2028: the start screen and the definition I previously showed. In the 2015 app, the bottom right button meant there’s an image available.

Back in the day, the online version had bugs, meaning that some definitions were truncated. I don’t know if they fixed it in the meantime (I hope so), because the website is the only decent way to read Il Vocabolario Treccani: the current app requires a subscription, despite being nothing more than a glorified browser that displays the mobile version of the website!

The nerve of them!

But speaking of cheekiness, remember that online dictionary made by one Enrico Olivetti from the Philippines? Well, he had the guts to publish an Android app and to ask for €10/month to access content that is free in any browser!

BTW, if you believed Android 16 could run those old APKs, you’re wrong:

But also (and so on):

Google is the most evil IT company, much more evil than Microsoft! They purposely sabotage backwards compatibility!

Back to using “to suggest”

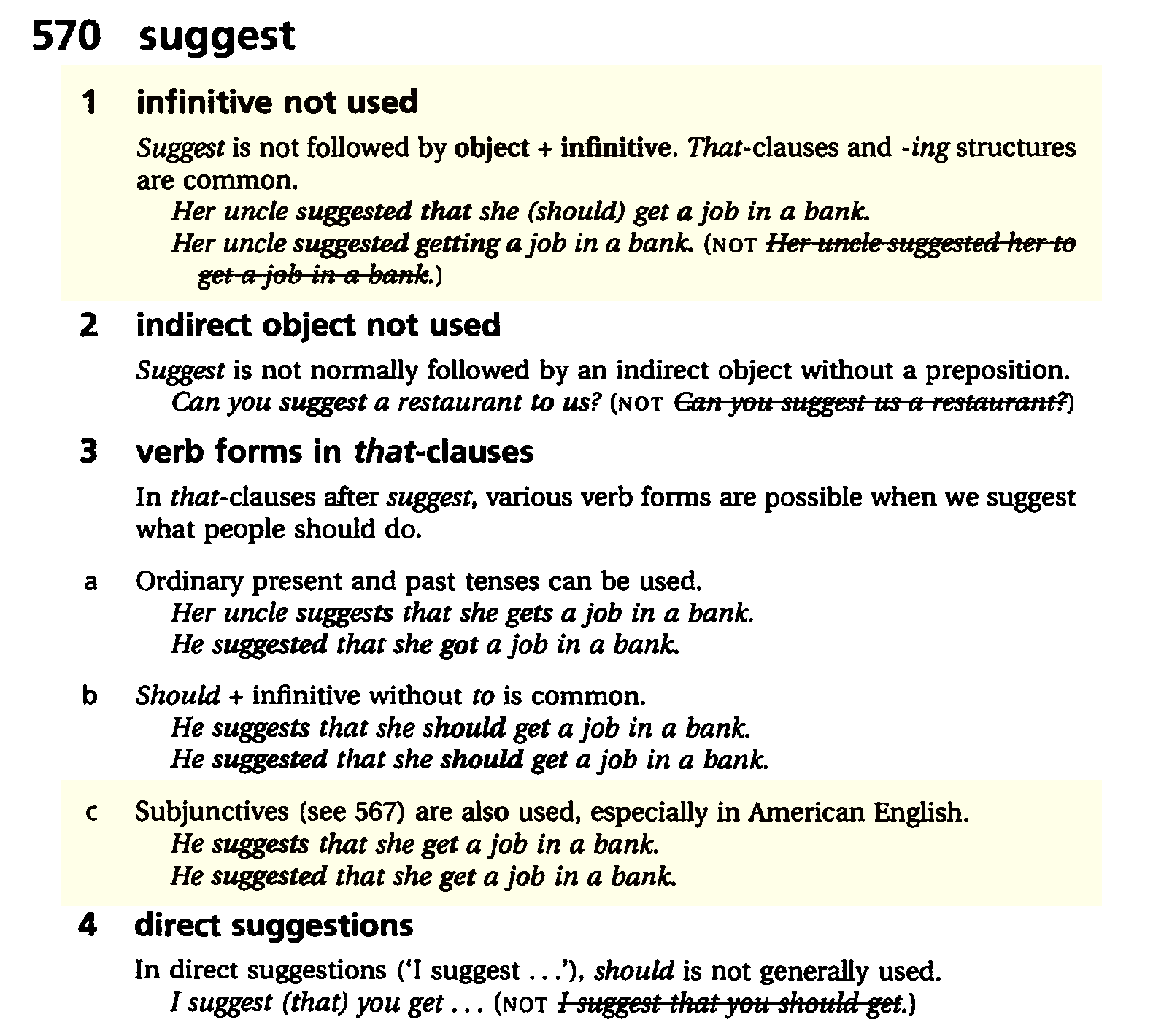

I started with the purpose of explaining why we should say, “This is from the first documentary I’m going to suggest you watch,” and not “This is from the first documentary I’m going to suggest you to watch.” And I explained that it’s a form of subjunctive. After such a long detour, I’m getting there.

❶ Let’s recap, even if this is from a dictionary, not from a grammar book:

Forms of subjunctive:

- Past subjunctive: “I wish I were…” / “I wish it were…” / “If I were…” / “If it were…” (not “was”).

- Present subjunctive with “that”: “We ask that each tenant take (not takes) responsibility…” / “It is important that only fresh spinach be (not is) used.” (In AmEn the use of “that” is optional.)

- Idioms: “So be it.” “Heaven help us.”

- “as it were…” to mean “in a way,” “so to speak,” or “in a manner of speaking.”

We’re in the second case, the present/mandative subjunctive. Let’s make this distinction:

- Past subjunctive = counterfactual

- Present subjunctive = mandative, with “that” (which can however be omitted).

❷ But there is a potentially puzzling situation: should you replace “suggest” with “tell,” the situation changes. “Tell” is commonly followed by an object + to-infinitive: “Please tell someone to do something.”

- “Can I suggest you go buy some coffee?”

- “Can I tell you to go buy some coffee?”

⁉️ But how are we supposed to know which verb behaves one way or another?

Well, you just do. Here’s a shortlist:

- Verbs followed by [object + to-infinitive]: ask, advise, encourage, persuade, remind, tell, warn.

- Verbs followed by [(that) + clause] or [verb-ing]: advocate, demand, insist, propose, recommend, request, suggest, urge.

The verbs behaving like “suggest” are about advice, necessity, or strong suggestion. They resist the object + to-infinitive pattern. Instead, they “trigger” either:

- (that) + subjunctive: “I suggest that he go,” or

- -ing form: “I suggest going.”

Some more examples:

| Verb | Subjunctive | -ing |

|---|---|---|

| advocate | She advocated that the law be changed. | She advocated changing the law. |

| demand | The teacher demanded that the student leave. | — |

| insist | They insisted that he stay longer. | (rare) |

| propose | He proposed that we start earlier. | He proposed starting earlier. |

| recommend | I recommend that she read this book. | I recommend reading this book. |

| request | They requested that she be present. | — |

| suggest | She suggested that he apply. | She suggested applying. |

| urge | I urge that he reconsider. | — |