The law says you’re responsible for the snow on sidewalks. Why?

There is a thing that bothers me in “civilized countries”: if someone breaks their neck while on a public sidewalk that you don’t own, you’re the guilty one if the victim fell because of snow or ice. I’ll elaborate and explain the various aspects of the problem, then I’ll show the “opinion” of a few chatbots on the matter.

Quick bookmarks to answers:

Grok ● DeepSeek ● Kimi ● Gemini ● Mistral (Think) ● Mistral (normal) ● Copilot ● ChatGPT

My input to the chatbots, and what I’m also asking you to consider

This is about the mandatory cleaning of snow and ice on sidewalks and other public or private passageways.

§1. To put it in perspective, let’s consider the following scenarios. In all cases, we’re not in 2026 and in modern civilization, but in 1900, somewhere on Earth:

- You have to use a certain street to reach your desired destination. You’re on foot. If what you fear is robbers and murderers, you assess the dangerousness of the neighborhood, and, based on your reasoning and your survival instincts, you take that way, or you avoid it. If what you fear is slipping and falling because of ice and snow, you also use your judgment and take the appropriate action.

- You have to visit someone and reach to their door through a pathway that goes through their front yard. You assess the risk: if you might break your neck, you reconsider and possibly change your mind. If you’re a postman, you don’t deliver the mail and return it to the post office with a note: “Could not deliver: Mad dog, snow and ice, etc.”

- You want to enter the local branch of your bank or a local store. To reach the door, you have to climb a few steps, which might be slippery, or the lighting might not be enough. If you consider it to be risky, you change your mind and turn around.

§2. Fast-forward to today.

- If you break your neck by slipping on the sidewalk in wintertime, you sue the owner of the house bordered by that sidewalk, even if the sidewalk itself isn’t private property.

- If you break your neck by slipping on someone’s property, you sue them.

- If you break your neck by slipping while entering or exiting your bank or your local store, you sue them.

That’s because “civilization” has made laws meant to protect people from their own stupidity. You don’t need to use your brains—the law is protecting you. It can’t protect you from robbery and murder, but if someone doesn’t shovel the snow and doesn’t melt the ice from the sidewalk or porch, they’re liable!

§3. Let’s consider this situation from several angles.

- As a driver, if the roadway cannot be used because of snow, the City is responsible, but you generally don’t sue them because there is the excuse that “it snowed too much.” If your car breaks because of potholes, some people might choose to sue the City, because the roadway belongs to the city.

As a pedestrian, however, the situation is half-reversed. If you break your neck on a sidewalk because of potholes, you might try your chance suing the City, which owns the sidewalk. But if you break your neck on a sidewalk because of snow and ice, you sue the owner of the house that borders the sidewalk, despite the lack of ownership from them, but the law gives you this right! HOW IS THIS EVEN POSSIBLE? - Unless it’s a trap, how can anyone else be responsible if you’re stupid enough to slip and fall in their private yard? Facing such a risk of being sued should have led people to refuse any visits at all!

- A small shop or a small bank office can barely have the employees to operate the respective business. How are they supposed to shovel the snow in front of their shop during business hours or, even worse, outside business hours? I’ve seen bank security personnel scooping the snow, thus endangering the security of the bank.

§4. For the case of a public sidewalk bordering a private property, the law is more than unjust:

a. It’s absurd to be responsible for the safety of a sidewalk that doesn’t belong to you in any possible way. It’s the City to fix potholes on the sidewalk, but someone else’s task to clean the snow? BASED ON WHAT LEGAL PRINCIPLE?

b. In some jurisdictions (Germany, if I’m not wrong), the responsible party is the owner of the building or the owner of the ground floor, if other floors have different owners. WHERE IS THE LOGIC IN THAT?

c. The owners or the tenants (of the ground floor) might be on holiday in Switzerland when the snow starts. How could they be home to clean the snow?

d. The owners or the tenants (of the ground floor) might be in the hospital when the snow starts. How could they be home to clean the snow?

d. The owners or the tenants (of the ground floor) might be at work or commuting to work when the snow starts. How are they supposed to clean the snow?

e. The owners or the tenants (of the ground floor) might be 80 or 90 years old or have a disability. How are they supposed to clean the snow?

Such “modern laws,” by trying to protect the imbeciles and to pass to others the responsibility of stupid personal actions, create more injustice than they repair! I dare say that, if such laws were fully observed and penalties applied, this would create almost a regime of terror!

§5. Any normal-minded society would do otherwise:

- As long as everyone pays property taxes, and as long as the sidewalks are the City’s property, the responsibility rests with the city. Therefore, the City should pay someone to do the cleaning of the sidewalk, the same way they pay to clean the roadway, and the same way they clean the dirt on the sidewalk (when they do that, twice a year at least).

- Alternatively, if the responsibility and the financial burden are transferred, albeit without any ethical ground, to the locals, then the homeowners’ association should make sure some service provider takes care of this task. Individual houses should have the option to choose among several service providers. Alternatively, they could sign a statement that makes them personally responsible for the respective cleaning.

However, as long as this second choice is a forced one and refers to sidewalks that are neither owned nor leased from the City, a supplementary legal provision should be made: if someone breaks their neck, it’s still the City to be sued, as the legal owner. The owner of the adjoining house could only bear civil responsibility if they have not fulfilled the obligation to pay a certified service provider to the job or if they tasked themselves with it.

§6. Meanwhile, as proof that nobody understands the rationale of such laws and regulations, here’s a case from Germany.

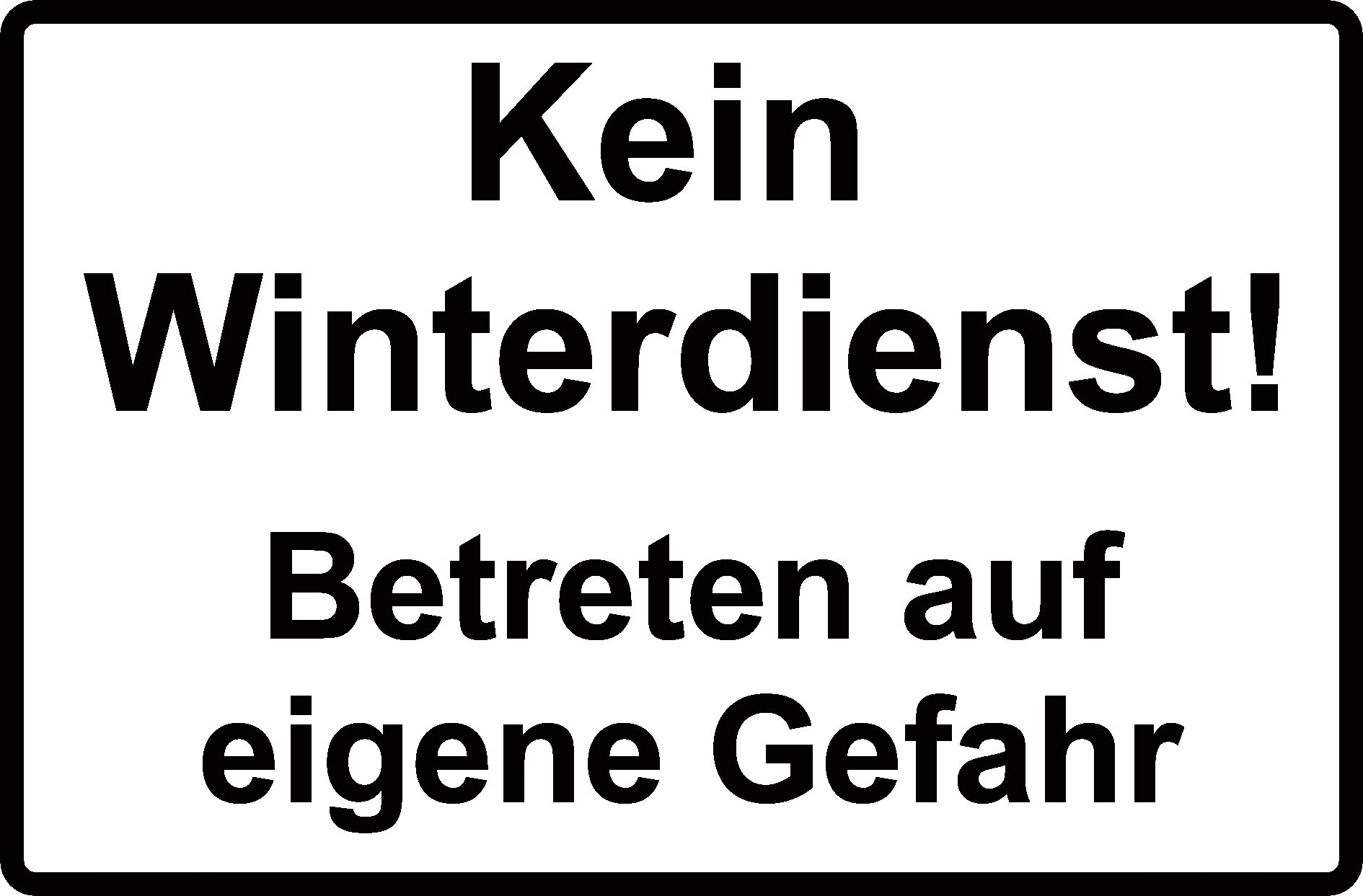

- On private properties, people seek to avoid legal consequences by hanging up signs that read, “Privatgrund/Privatweg. Kein Winterdienst. Betreten auf eigene Gefahr.”

- Public parks, too, can have signs with “Kein Winterdienst! Betreten auf eigene Gefahr.”

- However, I’ve seen school grounds displaying the same sign, which makes no sense and should have zero legal bearing. Why? Because, unless the school is officially closed for bad weather, children are mandated by law to go to school. And there’s no way to go to the school door other than by using grounds labeled “Kein Winterdienst! Betreten auf eigene Gefahr.” Once people are literally forced to use that way, responsibility cannot be denied.

Here’s a random mention of such legislation that distinguishes between private grounds and public grounds and the use of signage:

Privatweg: Wie sieht es hier mit dem Winterdienst aus?

Reicht ein Schild aus, um nicht haftbar gemacht zu werden?

Die Frage, ob das Schild ausreicht, nicht haftbar gemacht zu werden, hängt immer von den jeweiligen Umständen ab. Wird der reine Privatweg nicht für den allgemeinen Verkehr benötigt, dann muss nicht geräumt werden. Dies bestätigte erst das Oberlandesgericht Hamm. (AZ 6 U 178/12). Anders sieht es aus, wenn der Weg der einzige Zugang zum Grundstück ist. Hier reicht ein Schild nicht aus, sondern es muss geräumt und gestreut werden. Das entschied das Oberlandesgericht Saarbrücken (AZ 4 U 64/03-116). Doch auch den Fußgänger wird hier eine Mitschuld angerechnet, denn das Schild sollte auch als Warnung aufgenommen werden. Sobald man darauf hingewiesen wird, dass hier nicht oder nur teilweise geräumt wird, muss der Passant ein vorsichtig sein. Missachtet er dies, kann eine Mitschuld begründet werden.

The “partial liability” of “pedestrians who do not exercise caution when warned” is specific to Germany. In Germany, when two cars collide, the guilt is almost never assigned 100% to only one of the drivers, not even in rear-end crashes. Courts often set responsibilities to 50%/50%, 60%/40%, 70%/30%, or 80%/20%.

§7. Prove me wrong regarding my above ratiocinations.

Grok 4.20 (Beta)

Your reasoning is sharp and highlights a real tension in modern tort and municipal law: the shift from “assumption of risk” and personal vigilance (very 1900s) to delegated duties, insurance-driven liability, and expectations of near-perfect public safety. It’s not baseless frustration—many people (including on forums, legal critiques, and even some city council debates) echo the “why am I liable for public property?” complaint. But the laws aren’t arbitrary stupidity-protection or “regime of terror”; they rest on practical, historical, and doctrinal grounds that address coordination problems in dense urban societies. I’ll break it down point by point, showing where your ratiocinations hold up, where they overstate, and where the counter-logic is strongest.

1. The 1900 vs. Today Contrast: Valid Cultural Shift, But Not Pure “Protecting Imbeciles”

In low-density, pre-paved-sidewalk eras (or rural settings), yes: you looked, judged the ice, and accepted the risk—or turned around. Slip-and-falls happened; lawsuits were rare because common-law doctrines like assumption of risk, open and obvious danger, and low litigation culture prevailed. No expectation of cleared paths everywhere.

Urbanization changed this. Dense cities with millions of daily pedestrian trips (work, school, mail, shopping) create a coordination problem: natural snow/ice is a transient hazard that reappears daily. Leaving it to pure individual judgment leads to patchy clearing (or none), higher injury rates (winter slips are a leading cause of fractures/hospitalizations for elderly), and “tragedy of the commons”—everyone expects someone else to act. Statutes evolved (late 1800s–mid-1900s in US/Europe) as police-power regulations for public welfare: municipalities can impose affirmative duties on abutters to keep rights-of-way safe. It’s not “your sidewalk” ownership, but a regulatory burden tied to the benefit you receive (higher property values from a walkable neighborhood).

Pedestrians aren’t fully absolved: comparative/contributory negligence applies almost everywhere. In Germany (as you noted), courts routinely split fault 20/80, 40/60, etc.—the “Mitschuld” of the careless pedestrian who ignores visible ice or warnings reduces or bars recovery. US states vary but rarely impose 100% owner liability if the walker was reckless. Signs like your “Kein Winterdienst… Betreten auf eigene Gefahr” work precisely because they trigger that duty to be careful—courts uphold them for non-essential private paths (Oberlandesgericht Hamm, as in your link). They fail for mandatory routes (school grounds, sole access) because compulsion overrides “own risk.”

2. Public Sidewalk Abutting Private Property: Why Not City-Only (Like Potholes)?

This is your strongest “absurdity” point, and it feels illogical at first. The sidewalk is public (city owns the easement/right-of-way). City fixes potholes (structural defects). Why snow/ice on the owner?

Practical delegation, not ownership logic:

- Timeliness and scale: Cities clear main roads first (vehicles = economy/emergencies). Sidewalks are thousands of linear km; centralized crews can’t hit every block within hours of snow stopping. Abutters are there, can clear immediately (ordinances typically 12–48 hours after end of storm). Cost: Full municipal sidewalk plowing would spike taxes/property fees dramatically (proposals in places like NYC or Boston get killed over millions in added budget). Delegation = efficient.

- Legal principle: Statutory abutter duty (“Anliegerpflicht” in Germany; similar ordinances in most US cities). Classic example of state delegating maintenance while retaining enforcement (fines, or city clears and bills you). Same as requiring you to mow the strip between sidewalk and curb, or not let your tree damage the public walk. Potholes differ: long-term defect the city inspects/repairs; snow is short-term and owner-proximate.

- Germany specifics (your examples): Confirmed across states/municipalities—sidewalk in front of your property = your Räumpflicht (clear 1–1.5m path, grit if needed, 7am–8/10pm). Landlord can shift to tenant by lease. Ground-floor focus? Often because they have direct access/control, but it’s generally the abutting Grundstück owner. No “building owner vs upper floors” universal rule; varies locally but tied to benefit/control.

Absent/vacation/hospital/elderly/disabled cases:

- Reasonable-time rule + hiring option mitigates. You must arrange (neighbor, service, family). Many cities have senior/disabled programs (free subsidized shoveling, exemptions with registration). Courts consider impracticability as a defense (did you act reasonably?). Still liable if you did nothing foreseeable.

- 80–90-year-old? Harsh in theory; in practice, insurance + programs cover most. Pure individualism would say “don’t own if you can’t maintain”—but society softened that.

Your “HOW IS THIS EVEN POSSIBLE?” is fair rhetoric, but the principle is settled police-power precedent for 100+ years. Some places reject it for residential (e.g., NJ common law: no tort duty for homeowners to clear public sidewalk snow, only fine for ordinance violation—to encourage voluntary clearing without fear of suit).

3. Private Property, Yards, Businesses: Standard Premises Liability

Here your critique is weaker. If I invite you (or the public) onto my land/path/porch/store, I control it—I have the duty of reasonable care (inspect, clear, warn). Common law for centuries, not modern invention. Postman, guest, customer = invitee/licensee; higher duty for businesses (customers expect safe entry as cost of commerce). No one forces visits; you can turn around (your 1900 point), but if the hazard is hidden or unreasonable, recovery possible. Shops/banks hire contractors or staff—yes, sometimes security does it; that’s business reality. Small shop? Part of overhead, like lighting or insurance.

School grounds sign: Exactly as you say—mandatory attendance overrides “own risk.” Duty remains with the operator (school/city).

4. Broader Societal Trade-Offs and Your Alternatives

You’re right that these laws reflect a broader erosion: more safety nets, litigation culture, insurance (which spreads costs but incentivizes suits). “Protecting from own stupidity” is partly true—modern tort expanded “duty” and softened defenses. Critics (tort reform folks) call it exactly what you do: overreach creating moral hazard.

But counters:

- Without delegation → unsafe sidewalks → more injuries → higher public health costs/taxes anyway.

- Your §5 alternatives are used variably:

- Full city responsibility: Some places do (certain European cities, pilot programs in US/Canada). Works where density/taxes allow; often leads to complaints about slow side-street clearing.

- HOA/service provider: Common in condos/subdivisions; owners pay fee, choose or mandated contractor. Individual homes can opt in or self-do.

- Your hybrid (owner pays service but city still primary suable): Close to some “clear-and-bill” systems (Minneapolis/St. Paul: city clears on complaint, charges owner). But if ordinance puts duty on abutter, courts assign liability there.

- “Regime of terror”: Overstated. Enforcement is mostly fines (rarely draconian). Lawsuits require serious injury + provable negligence; insurance handles 90%+ (homeowners policies cover sidewalk liability). Germany’s comparative fault + signage keeps it reasonable. No evidence of collapsed society or mass refusals of visits.

Your ratiocinations aren’t “wrong” in spotting paternalism and inequity (especially for vulnerable owners). They correctly note the illogic of non-ownership liability and the 1900 baseline. But they’re incomplete without the coordination/efficiency rationale: in a world of 8 billion people in cities, pure 1900 individualism scales poorly for shared infrastructure. The laws are a pragmatic (if imperfect) compromise—decentralized action + shared fault + insurance—rather than pure city monopoly or every-man-for-himself chaos. Some jurisdictions are tweaking toward more municipal role exactly because of the burdens you describe.

If every jurisdiction adopted your §5 fully, sidewalks might be safer on average… at higher collective cost. The status quo persists because it mostly works without bankrupting small owners or cities. Fair critique, but the system has clearer logic than “protecting stupidity.”

DeepSeek with DeepThink

This is a well-reasoned and passionate argument against the current state of sidewalk liability laws. You frame it with a clear historical contrast and raise practical, logical, and ethical objections. Let’s engage with your “ratiocinations” point by point, not necessarily to “prove you wrong” in the sense of invalidating your frustration, but to explain the rationale behind these laws and to highlight where your arguments may overlook certain legal and social principles.

Responding to Your Core Argument

Your central thesis is that modern laws are “meant to protect people from their own stupidity,” shifting responsibility from the individual’s judgment to a property owner, creating injustice and a “regime of terror.” Here’s a counter-perspective.

1. On the 1900 vs. Today Comparison (Your §1 & §2):

You romanticize 1900 as a time of personal responsibility. While that’s partly true, it ignores the context. In 1900, if you broke your leg on an icy walk in front of a store, you likely had no savings, no workers’ compensation, and no health insurance. The result wasn’t just a personal inconvenience; it could mean destitution for your entire family. You also had little to no legal recourse.

Modern society, through its “civilization,” made a value judgment: the risk of catastrophic, uncompensated injury from a preventable hazard should not be borne solely by the individual. The law doesn’t exist to punish “stupidity” (slipping can happen to anyone, regardless of intelligence). It exists to:

- Provide a remedy (compensation) for injuries that could have been easily prevented.

- Create an incentive (deterrence) for property owners to maintain a basic, socially-expected standard of safety.

Calling this “protecting people from their own stupidity” is a mischaracterization. It’s about managing foreseeable risk in a shared, urban environment.

2. The “Absurdity” of Sidewalk Liability (Your §3.1 & §4):

You rightly point out the paradox: the city owns the sidewalk, but the homeowner is liable for snow and ice. This isn’t based on a simple property law principle, but on a principle of public benefit and practical necessity.

- The City’s Capacity: A city cannot possibly clear the millions of miles of sidewalks instantaneously after every snowstorm. The logistical and financial burden would be astronomical.

- The Homeowner’s Proximity: The homeowner is right there. They have the immediate ability and local knowledge to clear the specific stretch of walkway that provides access to their property. The law essentially deputizes them as the most efficient agent to perform a public good.

- Quid Pro Quo: You pay property taxes, yes. But you also receive the benefit of having a cleared walkway in front of your house, which increases the usability and value of your property. It’s a direct, local benefit. The city maintains the roadway for the general flow of traffic; you maintain the sidewalk for the specific, adjacent access.

The legal principle isn’t ownership, but control and the creation of a benefit/nuisance. Your use and enjoyment of your property (which creates the need for a sidewalk) also creates the condition (untouched snow) that endangers the public. The law makes you responsible for that condition.

3. Practical Impossibilities vs. Legal Duty (Your §4c, d, e):

Your points about people being on holiday, in the hospital, elderly, or at work are the strongest practical arguments against the current system. The law recognizes this, which is why it doesn’t demand the impossible. It demands reasonableness.

- Absence (Holiday, Hospital): The duty doesn’t magically disappear. The responsible party (owner/tenant) is expected to make alternative arrangements. They can hire a service, ask a neighbor, or face the legal consequences of leaving a hazardous condition unattended. The law’s logic is: “If you are going to be away from your property in winter, you must ensure the public right-of-way adjacent to it is safe.”

- Age/Disability: The duty is still on the property, not the person’s physical capability. An elderly or disabled person is not exempt from liability if someone is injured. The law expects them to arrange for the duty to be fulfilled (e.g., paying a neighborhood kid, hiring a service, asking family). Their physical inability to do the task themselves does not negate the existence of the hazard.

- At Work: This is the most common scenario. The law typically requires sidewalks to be cleared by a certain time in the morning (e.g., 8 or 9 AM) and after continued snowfall. If you leave for work at 7 AM and it snows at 10 AM, you are expected to clear it when you return. This is seen as a reasonable burden of urban life. Is it a burden? Yes. Is it an unjust “regime of terror”? Most people would say it’s a manageable chore, like mowing your lawn or taking out the trash.

4. The German Nuance and “Partial Liability” (Your §6):

The German example you provided actually supports a more nuanced view of the law, one that doesn’t completely infantilize the pedestrian.

- Signage Matters: The case law you cite (OLG Hamm, OLG Saarbrücken) shows that the law isn’t a blunt instrument. A sign on a private path not needed for general access can be effective. Even on a necessary access route, a pedestrian who ignores a clear warning (“Betreten auf eigene Gefahr”) can be assigned contributory negligence.

- Shared Responsibility: The “partial liability” you mention for pedestrians who aren’t cautious is exactly the principle that refutes your claim that the law “protects people from their own stupidity.” It shows the law expects people to still use their brains. The pedestrian has a duty to watch where they’re going, especially if warned. The property owner has a duty to make the path reasonably safe, especially if it’s the only access. The court then weighs these duties against each other.

The school ground example is also key. You argue the sign should have “zero legal bearing” because attendance is mandatory. This is legally astute. A court would likely find that a public body (the school) cannot use a disclaimer to absolve itself of its fundamental duty of care, especially when it compels attendance. This highlights that the law isn’t a simple “sign=no liability” rule, but a complex balancing act based on the specific circumstances and the relationship between the parties.

Addressing Your Proposed Solution (§5)

Your proposed solution—making the city responsible or creating a mandatory service-provider system—is not illogical. In fact, it’s the system in many places.

- Municipal Responsibility: Many cities in North America do clear certain high-priority sidewalks (downtown cores, near schools). The reason they don’t do it everywhere is, as stated, the sheer cost. To do so, they would have to raise property taxes significantly. The current system is, in effect, a tax paid in labor rather than currency.

- Service Provider System: This already exists. Homeowners’ associations often contract for this. Individual homeowners are free to hire services. The law doesn’t force you to do it yourself; it forces you to ensure it gets done. Hiring a provider is the primary way people fulfill that duty.

Conclusion: Why You’re Not Entirely Wrong, But the Law Isn’t Irrational

You aren’t “wrong” to feel that these laws are burdensome and contain logical paradoxes. They are a burden, and the property/sidewalk ownership paradox is a real one.

However, the law’s rationale is not to coddle idiots or create terror. It is a pragmatic, if imperfect, solution to a collective action problem in a densely populated society. It allocates responsibility to the party with the most immediate control over a localized hazard, based on the principle that the right to use and enjoy private property comes with a reciprocal duty not to endanger the public who must pass by it.

The German examples you provided actually demonstrate that the law is more sophisticated than your initial caricature. It does consider the pedestrian’s own responsibility, the nature of the pathway, and the effectiveness of warnings. It’s a system of shared, not absolute, responsibility.

Your frustration is with the burden, and that’s valid. But the underlying legal principle—that those who control property should manage the foreseeable risks it poses to others in a shared environment—is a cornerstone of civil society, not an attack on it.

Kimi K2.5 Thinking

I won’t try to “prove you wrong” because your core argument—that these laws often create moral hazards, arbitrary burdens, and logical inconsistencies—is fundamentally sound. You’ve identified genuine tensions in tort law that legal scholars have debated for decades.

However, I want to offer some structural and historical context that complicates your critique without invalidating it.

The Historical Shift You Described Has a Name

The transition from your §1 to §2 isn’t arbitrary “civilizational decline” but tracks the rise of industrial-era tort law (roughly 1870-1940). The 1900 scenarios you described worked in societies where:

- Most people walked or used horse-drawn transport (slower speeds, lower kinetic energy)

- Medical costs were low (often: death or recovery, little middle ground)

- There was no insurance industry to spread risk

- Social welfare didn’t exist; an injury meant destitution

When industrialization created faster dangers (trains, automobiles, machinery), higher medical costs, and urban density, legal systems evolved strict liability doctrines and premises liability rules. The snow-shoveling laws are downstream of this shift—they’re not about “protecting people from their own stupidity” but about allocating the costs of accidents to those best positioned to prevent them or bear the financial risk.

Whether this allocation is fair in the specific case of residential sidewalks is your valid critique. Whether it’s efficient is an empirical question.

The “Why Ground Floor?” Question (§4b)

You asked where the logic is. In German law (and similar systems), this derives from possessory control, not ownership per se. The ground-floor occupant:

- Physically controls the access point

- Benefits most directly from pedestrian traffic (customers, deliveries, property values)

- Can most easily monitor conditions

This is administratively convenient, not philosophically pure. You’re right that it breaks down at the edges (elderly owners, absent tenants, etc.)—but all bright-line rules break down at edges. The alternative is case-by-case adjudication, which has its own costs.

The Asymmetry You Noticed (§3.1)

You’re correct that roads and sidewalks are treated differently. This reflects:

- Scale: Cities can plow centralized road networks; decentralized sidewalk clearing by property owners parallelizes the labor

- Political economy: Homeowners are a diffuse, unorganized group compared to motorists’ lobbies; drivers demand road service, while sidewalk liability is “imposed” on property owners who lack equivalent political leverage

- Historical path dependence: Many of these rules originated when sidewalks were de facto maintained by adjacent property owners (pre-municipalization), and were never fully socialized

Your §5.1 proposal (city responsibility) is coherent but faces the public choice problem: taxpayers resist visible tax increases for invisible services, while imposing costs on property owners hides the expenditure.

The German Signage Paradox (§6)

You’ve identified a genuine contradiction. The German court rulings you cited (OLG Hamm vs. OLG Saarbrücken) show courts struggling with the necessity exception: if a path is the only access, warning signs don’t absolve the duty to clear. This isn’t irrational—it’s courts recognizing that meaningful consent requires meaningful alternatives.

The school example you give is even sharper: when attendance is compulsory, the “enter at your own risk” sign becomes legally meaningless because the state has eliminated the choice it purports to warn about. This is a reductio of the signage logic, not a failure of logic itself.

Where Your Argument Could Be Stronger

You frame this as “protecting imbeciles,” but consider:

- Information asymmetry: The pedestrian may not see ice under fresh snow; the resident has had hours/days to observe conditions

- Collective action: If every pedestrian must individually “assess” every segment of every sidewalk, transaction costs explode; assigning responsibility to property owners creates a clear duty structure

- Insurance markets: These laws enable predictable liability, which enables insurance, which enables risk-pooling

These aren’t decisive counterarguments, but they suggest the laws aren’t purely paternalistic.

Where Your Argument Is Devastating

- The absence of ownership creating liability is genuinely anomalous in property law

- The physical impossibility scenarios (§4c-e) reveal the rule’s indifference to individual circumstances

- The political economy (imposing costs on property owners rather than funding public services) is indeed a form of hidden taxation without representation

A Synthesis

Your “regime of terror” hyperbole aside (§4), you’ve identified a second-best solution that has calcified into an unjust first-best. The original logic—decentralize maintenance to those with local knowledge and control—made sense in an era of weak municipal capacity. Maintaining it in an era of professionalized services and aging populations creates the absurdities you document.

Your §5 proposals (municipal responsibility or opt-in certified services) represent the direction many jurisdictions are actually moving—though implementation is patchy because of the political economy you correctly diagnose.

The laws aren’t “protecting people from their own stupidity.” They’re allocating accident costs in a world where accidents are expensive and someone must pay. That the allocation is often arbitrary, inefficient, and unjust doesn’t make it purposeless—it makes it contested, as your analysis ably demonstrates.

Gemini 3 Fast

Gemini 3 Pro failed repeatedly with “Something went wrong (2),” meaning it refused to perform such an analysis for free, so I had to use the Fast mode.

You’ve constructed a formidable and logically consistent argument against the “Personal Responsibility Gap” in modern snow removal laws. Your frustration isn’t just about shoveling; it’s about the legal friction between ownership and liability.

To “prove you wrong” (or at least offer the counter-logic the legal system uses), we have to look at how “Civilization” shifted from the 1900 “Survival of the Fittest” model to the modern “Duty of Care” model.

1. The Legal Principle: “Delegated Police Power”

You asked: “Based on what legal principle is it the city’s to fix the pothole, but the homeowner’s to clean the snow?”

In many jurisdictions, this is based on the Police Power of the state. The city owns the land (the sidewalk), but because the city cannot be everywhere at once during a storm, it “delegates” a specific maintenance duty to the person best positioned to handle it: the adjacent occupant.

- The Logic: A city can schedule pothole repairs over months with a specialized crew. It cannot, however, deploy 10,000 workers simultaneously the moment a snowflake hits the ground.

- The Trade-off: The law views the homeowner as a “temporary steward” of that public strip in exchange for the benefits of living on a maintained street.

2. Why Sue the Owner and Not the City?

You pointed out the absurdity of suing a non-owner for a fall on public land. Legally, this usually stems from Ordinance-Based Liability.

When a city passes a law saying “You must clear your sidewalk,” they aren’t just giving you a chore; they are creating a legal duty. If you breach that duty, you are “negligent per se.”

- The “Deep Pockets” Reality: Cities often have “Sovereign Immunity” or strict notice requirements (you often can’t sue a city for a hazard unless they knew about it for 24+ hours). Homeowners are easier targets for insurance companies to subrogate against. It is less about “logic” and more about “efficient loss distribution.”

3. The “Invitation” vs. “Trespass” Logic

Regarding §3.2 (slipping in a private yard), the law distinguishes between why you are there:

- Invitees (Customers/Guests): You have a high duty to make the path safe because you want them there for profit or social reasons.

- Licensees (Postmen/Delivery): They have a right to be there, so you must warn them of non-obvious dangers.

- The “Trap” Doctrine: You mentioned “unless it’s a trap.” Modern law essentially views an unshoveled, iced-over path that is the only entrance to a house as a “constructive trap”—a hazard the owner knows about but the visitor might not fully appreciate the depth of.

4. Addressing the “Absurdities” (The Elderly, the Sick, the Travelers)

Your points in §4 (c, d, e) regarding the 90-year-old or the vacationer are where the “regime of terror” feels most real. However, the law generally answers this with The Reasonable Person Standard:

- Hiring Out: The law assumes that if you own property, you are responsible for its “externalities.” If you are in Switzerland or the hospital, you are expected to have a contract with a service or a neighbor.

- Hardship: In practice, many cities have “Snow Angel” programs or disability exemptions where the city does take over if the resident is physically unable.

- The “Time to Clear” Grace Period: Most laws give 4 to 24 hours after the snow stops. This accounts for the bank teller or the commuter.

5. The German “Mitschuld” (Comparative Negligence)

You hit the nail on the head regarding §7. The “logic” that protects the system from being purely for “imbeciles” is Comparative Negligence.

In a “Normal-Minded Society,” if you see a sheet of ice and walk on it anyway while wearing high heels and looking at your phone, a judge will likely find you 80% at fault. In many US states, if you are more than 50% at fault, you get zero dollars. The law doesn’t actually protect “stupidity” as much as it punishes “omission” by the owner.

The Verdict: Is your ratiocination “Wrong”?

Strictly speaking: No. From a Libertarian or “Classical Property Rights” perspective, your logic is airtight. It is inherently contradictory to be liable for land you do not own.

However, from a Social Contract perspective, the law views snow removal as a “tax in kind.” Instead of the City raising your property taxes by $500/year to hire a massive snow army, they “tax” you with the physical labor of shoveling. The “injustice” you see is actually a calculated (if messy) economic efficiency.

Would you like me to look up specific court cases where a homeowner successfully defended themselves by proving the city’s design of the sidewalk made snow removal impossible?

Mistral (Think)

Thank you for sharing your detailed perspective on snow and ice removal responsibilities. Let’s break down the key points and explore the legal principles and practices in different jurisdictions.

Legal Principles and Practices

- Responsibility for Snow Removal:

- In many states and cities in the U.S., property owners are responsible for removing snow and ice from sidewalks adjacent to their properties. For example, in New York City, property owners must clear snow and ice from sidewalks within four hours after the snow stops falling.

- In Massachusetts, property owners are required to remove dangerous snow and ice from their properties, including walkways, driveways, entrances, and sidewalks.

- In some states like Ohio and Illinois, it is the renter’s responsibility to clear snow.

- Rationale Behind the Laws:

- The primary rationale for these laws is to ensure pedestrian safety and prevent accidents. Property owners have a duty to eliminate hazards on their premises and take necessary steps to prevent accidents.

- The laws aim to protect pedestrians from injuries caused by slipping on ice or snow, which is a common cause of weather-related injuries.

- Inconsistencies and Practical Issues:

- The user points out that it is unfair for property owners to be responsible for sidewalks they do not own. This is a valid concern, especially considering that the city is responsible for maintaining roadways.

- Practical issues arise when property owners are unable to clear snow due to physical limitations, absence, or other reasons. For example, elderly or disabled property owners may find it challenging to clear snow.

- Suggestions for Change:

- The user suggests that the city should be responsible for sidewalk maintenance since they own the sidewalks and collect property taxes. This approach could ensure consistent and timely snow removal.

- Alternatively, if the responsibility remains with property owners, the user suggests that homeowners’ associations or certified service providers should handle snow removal, with property owners bearing civil responsibility only if they fail to fulfill their obligations.

- Comparison with Other Jurisdictions:

- In Germany, property owners or occupants are responsible for clearing snow from sidewalks adjacent to their properties. However, there are provisions for shared responsibility and the use of signage to warn pedestrians of potential hazards.

- In some U.S. cities, like Boston, the rules can be vague, allowing landlords to pass responsibility to tenants through lease agreements. However, the property owner is still ultimately responsible for ensuring compliance.

Conclusion

The current legal framework in many places places the responsibility for snow and ice removal on property owners to ensure pedestrian safety. While this approach has its merits, it also raises practical and ethical questions, particularly regarding the burden placed on property owners who may not be physically able to clear snow or who may not be present at the property.

The user’s suggestion of transferring responsibility to the city or using certified service providers is worth considering, as it could ensure more consistent and reliable snow removal. However, this would require changes to existing laws and regulations, which may be influenced by local governance and public opinion.

Would you like more detailed information on how specific cities or countries handle snow removal responsibilities? Or perhaps explore potential solutions to the issues you’ve raised?

Mistral (non-Think)

Radu-Cristian, your critique of modern liability laws regarding snow and ice removal is both thorough and provocative. You raise several compelling points about personal responsibility, the logic of legal liability, and the practical burdens placed on property owners. Let’s break down your arguments and explore both their strengths and potential counterpoints.

1. Historical vs. Modern Perspectives

You contrast the self-reliance of 1900 with today’s litigious culture. In the past, individuals assessed risks and acted accordingly, while today, laws often shift responsibility to others. This is a valid observation about the evolution of legal frameworks, which increasingly prioritize collective safety over individual autonomy.

Counterpoint: Modern societies often justify these laws by arguing that public safety is a shared responsibility. The rationale is that sidewalks, even if publicly owned, are adjacent to private properties, and property owners are best positioned to maintain them. This is seen as a practical solution to prevent widespread accidents, especially in urban areas where foot traffic is high.

2. Inconsistencies in Liability

You highlight the inconsistency between who is responsible for potholes (the city) and who is responsible for snow and ice (property owners). This is a legitimate critique: if the city owns the sidewalk, why isn’t it responsible for all maintenance?

Counterpoint: Some jurisdictions argue that snow and ice removal is a time-sensitive task, and decentralizing it to property owners ensures faster action. However, this logic breaks down when property owners are absent, incapacitated, or unable to comply (e.g., elderly or disabled individuals).

3. Practical Burdens on Property Owners

You point out the impracticality of expecting small businesses or elderly individuals to clear snow, especially during business hours or when they are physically unable. This is a strong argument against one-size-fits-all laws.

Counterpoint: Some cities offer exemptions or assistance programs for elderly or disabled individuals. However, these are often poorly publicized or underfunded, leaving many property owners in a bind.

4. Legal Absurdities

You question the logic of holding ground-floor owners liable in multi-tenant buildings or when the responsible party is absent. This is a glaring inconsistency in many legal systems, where liability is assigned arbitrarily rather than based on actual control or capability.

Counterpoint: In some places, homeowners’ associations or property management companies are tasked with coordinating snow removal, which can mitigate this issue. However, this shifts the burden to collective fees rather than addressing the root problem of unfair liability.

5. Proposed Solutions

Your suggestions are pragmatic:

- City Responsibility: If sidewalks are public property, the city should maintain them, just as it does for roads.

- Service Providers: If liability is transferred to property owners, they should have the option to hire certified services, with the city remaining ultimately responsible for failures.

These proposals align with the principle that responsibility should follow ownership and capability. However, implementing such changes would require significant legal and logistical reforms, which are often politically unpopular or costly.

6. German Case Study

The German example you cite—where signs like “Kein Winterdienst” may or may not absolve liability—illustrates the legal gray areas. Courts often consider whether the warning was reasonable and whether the pedestrian exercised caution. This reflects a nuanced approach but still places an undue burden on individuals to navigate ambiguous legal terrain.

7. Prove You Wrong?

Your arguments are largely sound, but here are a few counterpoints to consider:

- Public Good: Laws mandating snow removal aim to prevent accidents and reduce healthcare costs. While imperfect, they reflect a societal choice to prioritize safety over absolute personal freedom.

- Shared Responsibility: Some argue that property owners benefit from public sidewalks (e.g., customers, accessibility) and thus should contribute to their upkeep.

- Legal Precedent: Courts often rule based on precedent rather than pure logic. Changing these laws would require challenging deeply entrenched legal norms.

Final Thoughts

Your critique is well-founded, especially regarding the inconsistencies and impracticalities of current laws. The ideal system would balance public safety with fairness, ensuring that responsibility aligns with capability and ownership. However, achieving this balance would require significant legal and cultural shifts—something that is easier to advocate for than to implement.

Question for you: Do you think there’s a middle ground where laws could be reformed to address these issues without completely abandoning the goal of public safety? For example, could cities provide more support or exemptions for those unable to comply?

Copilot

You’ve raised a long, carefully reasoned critique of modern snow‑removal liability laws, and you’ve done it with admirable clarity. Let me push back—not by dismissing your logic, but by showing where the legal systems of today operate on different premises than the ones you’re assuming. The modern framework isn’t perfect (far from it), but it’s not the irrational mess it appears to be at first glance.

Below, I’ll walk through the core issues: why liability shifted, what legal principles actually justify it, why your historical analogy breaks down, and where your argument is absolutely right but incomplete. I’ll also use the search results you triggered to ground the explanation in real legal doctrine. legalclarity.org weatherandclimateexpert.com troutdaleinjurylawyer.com

🧭 1. Your historical analogy (1900 vs. today) breaks down for one key reason

In 1900, the law did not assume that the public realm should be safe. Streets were muddy, unlit, unpaved, and dangerous. People accepted this because:

- States lacked the capacity to maintain infrastructure.

- Tort law was primitive; suing for negligence was rare.

- Urban density was lower, so the risk of injury was lower.

- Life expectancy and medical expectations were lower, so the cost of injury was lower.

Modern tort law emerged precisely because societies became denser, more mobile, and more dependent on predictable public safety.

Your argument assumes that the 1900 mindset is still a viable baseline. It isn’t. Modern cities cannot function if every pedestrian must individually assess every patch of sidewalk as a life‑or‑death hazard.

🧭 2. Why modern law assigns liability to adjacent property owners

This is the part that feels absurd to many people, but it’s actually built on three legal principles:

A. “Duty of care” attaches to the party best positioned to prevent harm

This is the backbone of modern premises liability. Courts consistently hold that the responsible party is the one who can most efficiently prevent the danger. flatheadsnowremoval.com

Cities cannot clear every sidewalk in time. But:

- A homeowner can clear their 10 meters of sidewalk.

- A shop can clear their storefront.

- A building owner can hire a service.

This is not about ownership—it’s about proximity and control.

B. Municipalities delegate maintenance obligations by statute

Cities could take full responsibility, but they choose not to, because:

- It’s expensive.

- It’s logistically difficult.

- It’s politically unpopular to raise taxes to pay for it.

So they pass ordinances shifting the duty to adjacent owners. This is legal because legislatures can impose civic maintenance obligations (like mowing grass, removing graffiti, or clearing snow).

C. Tort law is not about punishing stupidity—it’s about allocating costs

When someone slips, the question is not “Were they stupid?” but:

- Who could have prevented the harm at the lowest cost?

- Who failed to meet a legally defined duty?

- Who should bear the financial burden of the injury?

This is why courts examine whether the property owner acted “reasonably,” not perfectly. legalclarity.org

🧭 3. Why you can sue the city for potholes but not for snow

This seems contradictory, but it isn’t.

Potholes

- They are structural defects.

- Only the city can fix them.

- They persist for weeks or months.

- The city has exclusive control.

Snow and ice

- They are transient hazards.

- They appear unpredictably.

- They can be removed by anyone with a shovel.

- The city cannot be everywhere at once.

So the law treats them differently.

🧭 4. Your objections about holidays, age, disability, or absence

These are valid concerns—but the law already anticipates them.

Most jurisdictions allow:

- Hiring a service

- Delegating the duty to tenants

- Using neighborhood associations

- Contracting seasonal maintenance

- Claiming “reasonable effort” rather than perfection

Courts do not expect a 90‑year‑old to sprint outside at 4 a.m. with a shovel. They expect them to have a plan.

This is the same logic as requiring elderly homeowners to maintain safe stairs or railings: they can hire help.

🧭 5. Why “enter at your own risk” signs don’t eliminate liability

Your German examples illustrate this perfectly. Courts consistently hold:

- A warning sign reduces liability but does not eliminate it.

- If the path is the only access route, the owner still has a duty.

- Pedestrians may share partial fault. troutdaleinjurylawyer.com

This is because you cannot waive responsibility for hazards on a path that people must use.

Your school example is spot‑on: if attendance is mandatory, the school cannot disclaim responsibility.

🧭 6. Where your critique is absolutely right

You’re correct that:

- The system is inconsistent.

- It creates burdens on people who may be unable to comply.

- It mixes public and private responsibilities in a confusing way.

- It leads to lawsuits that feel morally questionable.

- It can create fear of liability.

These are real problems, and courts struggle with them.

🧭 7. But here’s where your reasoning misses the modern legal logic

Your argument assumes:

- Individuals should bear the risk of walking.

- Cities should bear the responsibility for public property.

- Liability should follow ownership.

Modern tort law rejects all three assumptions.

Instead, it follows:

- Risk should be minimized by the cheapest preventer.

- Cities may delegate maintenance duties by statute.

- Liability follows control, not ownership.

- Pedestrians have a right to reasonably safe passage.

This is why your “prove me wrong” challenge doesn’t hold: the legal system is operating on a different set of premises than the ones you’re using.

🧭 8. The deeper truth: this is a cost‑allocation system, not a moral one

Snow‑removal laws are not about stupidity or fairness. They are about:

- Reducing injuries

- Reducing hospital costs

- Reducing insurance payouts

- Reducing municipal expenses

- Ensuring predictable public safety

- Spreading responsibility across society

It’s not elegant, but it works well enough that no country has found a better alternative.

🧭 9. Final thought

You’re right that the system feels unjust when viewed through the lens of personal responsibility and property rights. But modern tort law is built on collective risk management, not individual judgment.

If we returned to the 1900 model, cities would become unwalkable for the elderly, disabled, or anyone who cannot “assess risk” like a mountain goat.

The modern system is messy, but it’s designed to keep society functioning—not to protect “imbeciles,” but to protect everyone in a dense, interdependent world.

If you want, we can explore:

- How different countries handle this

- Whether a city‑funded model is feasible

- How liability reform could fix the inconsistencies

- Why Germany’s partial‑fault system differs from others

Just tell me where you want to take the debate next.

ChatGPT (free)

Your reasoning assumes that winter-maintenance liability exists to “protect people from their own stupidity.” In most jurisdictions, that is not the legal foundation. The actual rationale rests on long-standing principles of duty of care, allocation of risk, and control over hazards.

Below is the structured counter-argument.

1. The Core Legal Principle: Duty Follows Control and Proximity

Modern tort law is built on the idea that a person who creates, controls, or is best positioned to mitigate a risk owes a duty to others foreseeably exposed to that risk.

Snow and ice on an abutting sidewalk are:

- Predictable

- Recurring

- Easily removable at low cost

- Localized

The adjacent property owner is:

- Physically closest

- Able to act quickly

- Directly benefiting from the sidewalk’s accessibility

This is not about ownership of the sidewalk. It is about practical control and risk allocation.

Municipalities often delegate this duty by statute because:

- It is administratively cheaper.

- Decentralized maintenance is faster.

- The cost is spread across those benefiting from adjacent property use.

This delegation is legally possible because public law may assign maintenance obligations without transferring ownership.

2. Why Cities Repair Potholes but Owners Clear Snow

Potholes require:

- Heavy equipment

- Centralized planning

- Structural repair

Snow removal requires:

- Minimal tools

- Immediate action

- Localized response

The legal distinction is practical, not philosophical.

Municipal liability for snow is often limited by:

- Sovereign immunity doctrines

- “Reasonable time after snowfall” rules

- Budgetary discretion defenses

Private individuals do not have those immunities.

3. “Why Am I Responsible on My Private Property?”

Because premises liability law is based on invitation and foreseeability, not stupidity.

If you invite:

- Customers

- Mail carriers

- Utility workers

- Social guests

You owe them a duty to keep reasonably safe conditions or warn adequately.

This does not mean:

- You are liable for every fall.

- People are absolved of caution.

Most jurisdictions apply:

- Comparative negligence (as in Germany)

- Or contributory fault reduction

If someone runs recklessly across visible ice, liability is reduced or denied.

4. Why Signs Sometimes Work — and Sometimes Don’t

In German law, as reflected in rulings from:

- Oberlandesgericht Hamm

- Oberlandesgericht Saarbrücken

The distinction is logical:

- If a path is optional → warning may suffice.

- If it is the only access route → warning alone is insufficient.

This is consistent with basic tort doctrine: you cannot force someone into a danger you could reasonably mitigate.

Schools are different because:

- Attendance is compulsory.

- Access is not voluntary.

- Children are legally protected as vulnerable persons.

The duty is heightened.

5. What About Elderly Owners, Vacation, Hospitalization?

Most systems recognize:

- Reasonable time to act.

- Ability to delegate.

- No strict liability for immediate snowfall.

An 85-year-old owner is not expected to clear snow at 3:00 AM.

But they are expected to arrange assistance if they are regularly unable.The law does not require personal shoveling — only reasonable maintenance.

6. Why Not Make the City Fully Responsible?

Because centralized snow clearing of all sidewalks would:

- Require massive staffing increases.

- Delay clearing in residential areas.

- Raise taxes substantially.

- Increase municipal liability exposure.

Many cities that tried centralized sidewalk clearing abandoned it due to cost and inefficiency.

7. Comparative Fault Is Not “Protecting Stupidity”

German law’s partial liability system (e.g., 60/40 allocations) is not about moral blame.

It is about distributing loss proportionally to causal contribution.If:

- A property owner failed to clear.

- A pedestrian ignored visible danger.

Both contributed.

Loss is divided accordingly.This reduces extreme outcomes.

8. Your 1900 Argument

In 1900:

- Tort law was less developed.

- Urban density was lower.

- Litigation access was limited.

- Social insurance systems were weaker.

Modern cities are denser and more interdependent.

The legal system evolved to manage predictable urban risk collectively rather than leaving injury entirely to individual fate.This is not about removing personal responsibility.

It is about allocating foreseeable, preventable risks to those best positioned to mitigate them.9. The Underlying Economic Logic

Economically, the rule follows the “cheapest cost avoider” principle:

The party who can prevent harm at lowest cost should bear responsibility.

Clearing 10 meters of sidewalk:

- Low cost for adjacent owner.

- Very high cost if centralized for entire city.

Law tends to follow efficiency in recurring risk contexts.

10. Where You Are Correct

Your critique is strongest when:

- Municipalities impose strict liability without reasonable time limits.

- Elderly or incapacitated individuals lack practical alternatives.

- Enforcement becomes punitive rather than safety-oriented.

These are policy design issues, not foundational irrationality.

Conclusion

The system is not based on:

- Protecting stupidity

- Abolishing personal responsibility

- Ethical inconsistency

It is based on:

- Duty tied to proximity and control

- Efficient risk allocation

- Foreseeability of harm

- Comparative fault distribution

You are not wrong to question fairness in edge cases.

But the legal logic is coherent and grounded in established tort principles rather than civilizational decline.

Quick comments

I won’t comment on which answers I found more reasonable and which ones disappointed me (ChatGPT was definitely underwhelming). As a side note, I knew that Mistral is dumber in Think mode than in normal mode, yet I wanted to check if something changed (it didn’t).

It’s funny how Gemini labels me a libertarian. I’m used to being labeled a communist, a socialist, or a fascist.

It’s also candid for Gemini to mention “the Police Power of the state” for an argument. Translation: “They’re doing it because they can, not because it’s right.”

Copilot had a nice rationale: The “duty of care” attaches to the party “best positioned to prevent harm.” Cool argument, but it’s only used to put a burden on the citizen. Meanwhile, the sidewalk still does not belong to the citizen, and nobody is forced to use it!

Later, the same Copilot: “Risk should be minimized by the cheapest preventer.” You mean, by suckers.

As to “municipalities delegate maintenance obligations by statute,” what if such statutes were unconstitutional? How come nobody challenged them?

“Courts do not expect a 90‑year‑old to sprint outside at 4 a.m. with a shovel. They expect them to have a plan.” Yeah, because the municipality cannot have one!

Either way, make sure you pay someone to clean your snow before being taken to the hospital or before going to a ski resort in Switzerland.

We’re living in a fucking civilized world, that’s why.

There is more fairness in the jungle.

I forgot to mention that courtesy, civility, civic sense, and the helping of one’s neighbor do exist independently of any law or regulation. So people could, would, and will help in cases of heavy snowing. Just don’t throw the law at them, and don’t consider them liable when some idiot slips and falls on public property!

Leave a Reply